MFA Reading at 123 Pleasant Street

Each year, a new incarnation of COW (the Council of Writers) organizes events for the MFA and WVU writing community to gather and share their work. On Wednesday, September 30, the 2015–2016 COW officers hosted their first event, the annual fall MFA reading, this year at 123 Pleasant Street. Students and faculty enjoyed a relaxed evening, mingling around the bar and listening to selections from the students’ recent writing.

COW president Andrea Ruggirello introduced the evening and invited third-year students to read after breaking the ice with the questions third years dread: “So, what are you going to do after you graduate?”

Whitney Arnold, COW vice president, introduced the second years by sharing the questions they are tired of hearing: “How are you liking Morgantown?”

Megan Fahey, secretary, introduced the first years, encouraging them to take full advantage of their time at WVU.

First-year Jake Maynard closed the evening, not with his fiction, but with his skillful banjo-playing—the career alternative that made creative writing look practical.

First-year students from left to right: Jake Maynard, Natalie Homer, and Maggie Montague

Second-year student from left to right: Megan Fahey, Whitney Arnold, Kelsey Englert, Elizabeth Leo, Sarah Munroe, Andrea Ruggirello, and Kelsey Liebensen-Morse (COW treasurer).

Meet the MFA Class of 2018!

WVU is pleased to welcome seven new MFA students across three genres. Take a moment and get to know them through their bios below.

POETRY

Natalie Homer is from the ugly part of Idaho. She went to Idaho State University and earned a degree that is currently being used as a placemat on her dining room table. She is a fan of cats, rain, and catching up to the person who cut her off in traffic. Favorite authors include Matthew Quick, Ray Bradbury, Stephen King, Michael Dickman, Amber Tamblyn, Beth Bachmann, and others.

Natalie Homer

CREATIVE NONFICTION

Maggie Montague is from Fallbrook, California, the avocado capital of the world (or so they believe). She received her BA in English with a minor in art history from Whitworth University in Spokane, Washington. After graduating, she spent all her money on a plane ticket to Ireland and rode a bicycle for the first time in over ten years. Moving to West Virginia marks her first adventure on the eastern side of the country and her first home in a landlocked state. Item number one on her bucket list is to go on an archaeological excavation in Egypt. Maggie’s favorite writers include Elie Wiesel, Jack Gilbert, Annie Dillard, and Zadie Smith.

Maggie Montague

Meredith Jeffers grew up in Rochester, New York, the second snowiest city in the country, and attended college in the snowiest. She recently developed a severe lactose intolerance and still has not figured out how to pour soy into her coffee without it curdling. She most admires the work of Cheryl Strayed, Roxane Gay, Donna Tartt, and Jennifer DuBois, although she has soft-spot for popular mysteries—think Gone Girl and Luckiest Girl Alive.

Meredith Jeffers

Kat Saunders holds a BA and MA in creative writing from Ohio University. She is a first-year contributor to The MFA Years and serves as the associate fiction editor for Stirring: A Literary Collection. In her spare time, she enjoys cooking, taking baths, and asking her cat questions. Some of her favorite writers include Jo Ann Beard, Rebecca Solnit, Bonnie Jo Campbell, and Haruki Murakami.

FICTION

Nat Updike has never known what she wanted to be “when she grows up.” Starting in the field of civil engineering, she changed her focus to literature, creative writing, and philosophy. She then earned her BFA in creative writing and literature from the University of Evansville in 2012 and her MA in English at the University of Tennessee, Knoxville in 2014. After graduating from the University of Tennessee, she taught EFL in Colombia, South America as part of the Peace Corps from 2014–2015. Afterward, she taught ESL at the University of Southern Indiana and worked with people with disabilities at the ARC of Evansville, to save up money and begin her MFA in fiction writing at West Virginia University. When she’s not reading English 101 student papers or going to classes or religiously writing her second novel manuscript, she’s hiking, reading Nikki Giovanni poetry and art history, watching anything dystopian, especially The Walking Dead, volunteering, debating the mystery of Lost, wishing to do construction work in El Progresso, Honduras, thinking about Lemony Snicket, or drinking more coffee. She still doesn’t know what she wants to be “when she grows up,” but she hopes to teach creative writing and literature, earn a BA in philosophy, travel to Egypt, publish her manuscript, and own a Dyson vacuum cleaner someday.

Nat Updike

Jake Maynard grew up in a town of 800 people near Pennsylvania’s Allegheny National Forest. He started writing fiction after spending a summer working in a salmon cannery in the Alaskan bush. Since graduating from Hiram College in 2010 with a BA in history, Jake has acquired a border collie and a 1988 Chevy Blazer. His favorite books are Kurt Vonnegut’s Slaughterhouse Five and Halldor Laxness’s Independent People.

Jake Maynard

Bryce Berkowitz has a BA in creative writing from Columbia College Chicago. He moved to West Virginia from Los Angeles, where he worked at a talent and literary agency. He’s interested in recounted details surrounding crime related stories and events—interviews, undefined116122.undefined116123.undefined116124.undefined116731.undefined213152.documentaries, journalism, oral history, etc. Berkowitz currently admires the work of Danez Smith, Saeed Jones, Phillip B. Williams, Stuart Dybek, Richard Price, and Claire Vaye Watkins.

A Reading with Faith Shearin and Mark Brazaitis

The Robinson Reading Room was full on the evening of Wednesday, September 9, where an audience was gathered for the first reading of the season, which featured poet Faith Shearin and our own Mark Brazaitis.

Before Mark read, he relayed the story of how he came to know Faith’s work: The year was 2002. After entering a manuscript into a poetry contest, Mark (who has some experience winning writing contests) was disappointed to be named a finalist, not the winner. When they sent him a copy of the winner’s book, he expected to find that his poems were better. But, page by page, he saw they had chosen correctly. The winner of the May Swenson Award was Faith Shearin, and the book was The Owl Question.

For this event, however, Faith chose to mostly read poems from her newest collection, Telling the Bees. Introduced by second-year poetry student, Elizabeth Leo, Faith’s work, which tells the stories of what it means to be human, is tender and inviting but can also be brutal, inviting a different perspective about the world. Faith is a resident of West Virginia and the author of four books of poetry. Her work is regularly featured on Garrison Keillor’s radio program, The Writer’s Almanac.

Mark was introduced by second-year fiction student Megan Fahey, who described his work as being marked by simplicity and elegance (and I would add, often humor). When asked by students how to publish a book of stories, Mark’s reply was “I don’t know, just win contests I guess.” And that’s how Mark does it. He has won, among others, the Iowa Short Fiction Award, the ABZ Poetry Prize, the Gival Press Novel Award, and a distinguished story placement in Best American Short Stories.

Displaying his talent across genres, Mark read a poem about the golden toad between two short stories. The first story featured Chuckles, the killer cat. The second story, “Meet,” about what happens when fathers get involved in their children’s track meet, is from Truth Poker, which won the 2014 Autumn House Fiction Prize and came out at the beginning of this year from Autumn House Press.

You can listen to the reading on the Center for Literary Computing’s Creative Readings podcast.

Annual MFA Meet-and-Greet

To ring in the new academic year and welcome new and returning students and faculty after the summer break, MFA director and professor Mary Ann Samyn welcomed us all into her home for the annual MFA Meet-and-Greet on Saturday, August 29. Everyone enjoyed the opportunity to catch up in a casual atmosphere.

As usual, the event was well attended and well supplied with Mary Ann’s homemade tasty treats and salads.

Thank you for hosting us!

Hanging With Glenn Taylor: A Night of Launches and West Virginia Pride

On Wednesday, August 26, current and past students, West Virginia natives, and faculty (even WVU president Gordon Gee made an appearance) all packed in together at local favorite 123 Pleasant Street to hear Glenn read an excerpt from his new novel, A Hanging at Cinder Bottom, now out from Tin House. The event mirrored Glenn: warm, open, enthusiastic, and filled with genuine excitement. It was evident from the turnout that Glenn is adored by colleagues and neighbors alike.

Former student John Bryant introduced Glenn, reminding the audience of Glenn’s simple but straightforward advice: Write a good sentence. John was also sure to remind the audience of Glenn’s eagerness—or is it cutthroat attitude?—on the basketball court. The reading was accompanied by current WVU MFA poet Barrett Lipkin, better known by his basketball moniker “Feets,” on background guitar. During the reading, Glenn paused and laughed at certain points, as if reminded of his own ballsiness and wit. And several times, the whole crowd was laughing out loud.

The reading itself lasted about twenty minutes, at which point, Glenn put on his “singing hat” and did quite a respectable version of “Oh Hang Me” with lyrics changed to mirror the characters in his book. To conclude, Glenn, who had promised to launch the Cinder Bottom custom embroidered t-shirts (hand sewn by his wife Margaret) out of a slingshot, told the crowd that he’d had some trouble finding a slingshot big enough to accommodate the prizes for the raffle winners. Glenn then illustrated this by showing off several large, handmade contraptions, including a slingshot made out of exercise bands by MFA student Kelsey Englert. With egging on from the crowd, the t-shirts were launched, to various degrees of success but overall hilarity. At 7:45 Glenn Taylor announced it was past his bed-time.

Please join us as we congratulate Glenn and wish him success with Hanging at Cinder Bottom. Read the New York Times review, and purchase the book directly from Tin House (or through Amazon).

Contributed by Kelsey Liebenson-Morse

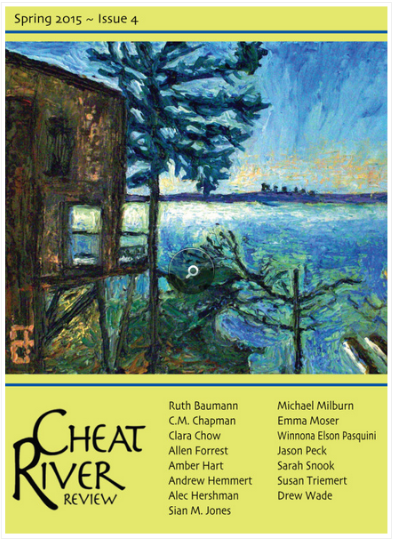

Do you Cheat River Review?

The Cheat River Review is the online literary magazine of WVU’s English Department. Currently in preparation for the fifth issue, its staff made up of MFAs, MAs, and PWEs considers pieces of fiction, poetry, creative nonfiction, as well as flash fiction, tiny poems, and cover art. CRR has published work by both emerging and established writers from places as near and far as Baltimore and Singapore.

Founded in 2013, the magazine takes its name from the Cheat River, a waterway local to the Morgantown area. As a young publication, CRR’s voice remains a work in progress. The staff does, however, look to publish stories that, as one clever editor once said, tell it to us interestingly. We’re not a West Virginia or Appalachian themed journal, but we are actively planning to engage with other local literary magazines and the WVU and Morgantown writing communities through literature events and readings over the next year and beyond.

Submissions for Issue 5 are open through mid-October; guidelines are on the website (unfortunately we can’t accept submissions from current or past WVU MFAs). Check out the Cheat River Review website to read our current and past issues and our blog, and look out for an Issue 5 release party this fall!

Contributed by Maggie Behringer, Editor-in-Chief, Cheat River Review

The cover of Cheat River Review Issue 4

Cover art by Allen Forrest, Bellevue Landscape #3, oil and canvas panel, 9” x 12”

Welcome Christa Parravani, New CNF Professor

Holding an MFA in Creative Writing from Rutgers University–Newark, as well as an MFA in Visual Art from Columbia University, new creative nonfiction faculty-member Christa Parravani relocated from Santa Monica to Morgantown this summer with her husband Anthony Swafford and daughter Josephine. Christa is the author of Her: A Memoir—an NPR, O, and People Magazine must-read memoir—and she’s jumping right in to teach the graduate CNF workshop this fall. I caught up with Christa at the beginning of August in her home in South Park to welcome her to WVU and to get to know her (guilty pleasure: the TV Land show Younger, which she only watches when she’s home alone), where she’s coming from, where she’s going, and how she approaches teaching. Read the Q & A below.

You’ve lived in New York City and most recently L.A. Morgantown must be quite a change. What do you miss about LA?

I made some really good friends in LA; I miss a few of my friends and the ocean. That’s true. I’m not gonna lie, I do miss the ocean. I don’t really miss Los Angeles. I miss New York City more than I miss L.A. New York City feels like home to me. It’s the only place in my entire life that’s really felt like home. There’s also—even though I’ve moved from a city—less longing for a city.

So far, what have you enjoyed in or about Morgantown?

Well, to me it seems like a really complicated place. The ecosystem of it feels wholly satisfying to me in that it’s equal parts beautiful and cursed. It’s haunted, but it’s totally alive and green, and the mountains seem to have a life of their own. I really love that, I appreciate it. I feel like I’m in a place that has a rich cultural history that I as a woman not from West Virginia don’t really know yet, but I can feel it here, and that’s really exciting to me. Yeah, I look forward to being able to be part of that. There’s a long history of great writing here. And living here I can see it, I can see why, it’s in the water. I don’t know what is in the water exactly, and I don’t know if I want to find out—do I want to know? But I feel that in a really immediate way, and it feels right to me.

You were in the MFA program at Amherst for a year, right? And for poetry there? What made you switch to prose, and how do you see poetry and nonfiction as connected?

I had written poetry for a long time. I had started writing poetry as an undergraduate at Bard, and my mind works in poetry, and lines. My entire life it’s been that way. Eventually it kind of transitioned between hearing something in a few words and trying to imagine something in a picture, but then what happened is I didn’t want to take photographs anymore. I had been a photographer, and I found there was a time in my life where I couldn’t use my camera anymore. My sister had died, and I couldn’t remember—it sounds insane—but I couldn’t remember how to use the camera. Honestly, my hands wouldn’t work. It was too heavy. I was too thin. It was too much. I stopped. And then I started writing poems. And they were sad, you know. They were poems about losing my sister. I put together a portfolio of poems and applied to UMass thinking that I would never get in, and I did, and I got a full scholarship. I thought, Oh my god, how can I not go? This is an amazing program, maybe these poems are alright!

I studied with James Tate, and I learned an extraordinary amount about writing during the short time that I was there. But the thing that I knew—I’d written this poem, and the poem was a poem about my sister. She was out on the sidewalk in Massachusetts where we lived, and there was a furious snowstorm, and she was meeting Abraham Lincoln under the streetlight. It was a really funny poem, and it was kind of suggestive because she was exposing herself to Abraham Lincoln. It was funny. I thought, You know, I think I’m ready to write something a little longer because the sort of presence of humor in these poems is telling me that I’m ready to touch on a subject to me that feels like it’s bigger than these poems can be.

My sister also went to UMass. She was a fiction student. If I was going to stay in the program and write about my sister in a meaningful and extended way, I was going to have to study with her professors. I just felt like I couldn’t do that. It wouldn’t have been fair to anybody. It was not going to be fair to me because I would have felt like I was there in her stead, if that makes sense. And it wouldn’t have been fair to them because they knew her and they grieved her. So, I had this amazing opportunity when I decided to leave UMass. I had met Jayne Anne Phillips at MacDowell [Colony] years before. I’d met her the year my sister died actually, and she kind of decided I was a like a daughter to her. She was my second mom. She has a great MFA program at Rutgers–Newark. I knew that if I went there I would have a good, safe place to write the book. So I went to Rutgers–Newark knowing that I was going to write Her, and that’s the only thing that I worked on while was there.

Jayne Anne is an excellent example of a writer—even though she writes fiction, she started out as a poet actually—a writer who puts the emphasis on the line. For me, the building of an essay or a book, any kind—I’ll write fiction as well—the emphasis is on building the story line by line. You’re like an architect, if that makes sense. And so I still use poetry, but it has to be sustained in prose in a way that can last. You can’t have the volume turned up as high in places. You have to modulate a little bit differently. For me, it’s always about the poetry of the sentence and the sound of the sentence. I don’t really separate those. I don’t really write poetry anymore, but I don’t separate the process of writing poetry and nonfiction that way because they feel really similar to me.

How do you approach teaching writing, then? What should your students know about you as a professor? How does your own process translate to your teaching?

My husband makes fun of me very often for having this skill—it’s a skill, I have a skill—my skill is that I can sit down with a complete stranger and they’ll tell me their life story in ten minutes. Consistently over my life, I have this skill. I’ve sat on buses and I’ve heard everything. I will call the Comcast help line and all the sudden I know all about somebody’s breakup. It’s kind of hilarious, but it always happens. It happens to me at least once a week. With that said, what students should know about me is that I’m listening. I think part of my strength as a teacher is that I listen and perceive information. I try because I care to help my students make the thing that they need to make—not the thing that I think is necessarily the best thing in the world, but the thing that I need to help them create. I think it takes a certain amount of empathy to be able to do that, and I’m tough. It’s a swirl of those sorts of things. I hope will help students. Also, for me, I like to think about what it means to be a citizen of the world. It’s important to me to be able to help people. And I see my teaching as part of that because had I not been ushered through by my great teachers, I wouldn’t have the life that I have right now, and I know that it’s really important. It’s not to be taken lightly. I approach my students with that in mind. I really can’t think of a better job, honestly.

Would you share a memorable moment from a mentor—or a bit of advice or an anecdote from those meaningful to you in some way, please?

God, there’s so many. There’s always one from every year from the time that I was a little kid til being a grown-up. If it wasn’t for my first really good teacher in high school, I probably would have gone to community college and become a hairdresser. I’m telling you the truth. The emphasis was not on education in my family, it was on just getting by and trying to figure out how to do it practically. I had a teacher who noticed that I had a gift for writing, and he helped me apply to colleges. He helped me find the colleges I could afford and the ones that would give me financial aid. I went to those colleges, and I made it. That was huge. He changed my life. I still call him. I thank him; he’s very meaningful to me.

Sometimes I think teachers know things that you don’t know. I remember that it was the first day I started graduate school and Jayne Anne was my teacher that semester. I said, This is it, I’m going to write this book, and this is the only book I’m every going to write. And she said, Come on. There are going to be at least a dozen more. I just didn’t believe her. And it’s so funny, because now when I sit down—I’m working on my second book and it’s hard, writing the second book is hard—I think about her standing near the coffee machine at Rutgers Newark insisting that there would be more books, and I feel like I just can’t disappoint her.

It’s good to have something—Oh yeah, you told me I have to.

Well it’s funny because I do have to. But she knew that, and I didn’t know that.

So, what are you working on now?

Well, I’m working on a second memoir; I’m about three-quarters of the way finished with it. It’s a book about growing up on a Marine Corps base. I grew up on Camp Lejeune, North Carolina, the daughter of a very strict Marine. That is the book that I’m working on, and I’m struggling. Oh man. It’s so hard. I think it’s a challenge to set yourself up to write your second book as a memoir after having published a memoir, and I didn’t see that when I embarked on it. Now I feel like I know people will read it and they will know things about me. Before I wrote like nobody would ever read it, which is the better way to do it. I’m really wrestling with it at this point and finding myself drifting a little bit. What I wanted to write was a really straight forward coming of age memoir about growing up on a Marine Corps base. Okay, I can do that, I’ve read so many. But then, there’s this thing that happened when I sat down to write, which is that I realized that my life is bigger than that. I’ve married a Marine. My husband is a veteran of the first Gulf War. What do you do with that? I’m on page 180 now, but I’m thinking, Gosh, I know a lot more about the subject than I’m letting on. Which then, I feel like, How do I restructure the book to say that? Do I need to restructure the book to say that? Should I talk about it? All the questions that are coming up as I’m writing are exciting ones to me, but I don’t know the answer yet, and some part of me feels like maybe I don’t know yet. Even though it’s a book about something that happened a really long time ago, it’s also about what’s happening now. And maybe I need some time.

How is it having written a memoir, having Her out there? People know about you, your students probably read it. How does that . . . I’m scared to write nonfiction because what if someone reads this who knows me?

You just have to be fearless—don’t think about them. One thing I know for sure is that when you’re thinking about what other people will think when you’re writing, you’re just procrastinating. Partially the person you create is not you. It’s the version of you that suits the narrative. To me, I wrote this book, but I’m not that. I mean, I’m a lot funnier than that person is. People are surprised, they’re like, You’re funny! I had no idea. Well yeah, I know, I just couldn’t manage that this time. But there is something a little strange about knowing that people feel close to you after reading something that you’ve put out into the world and you’ve never met them. What I assume when I—because my husband is also a memoirist—this is what I assume when I meet somebody after I’ve read their book: that I don’t know them, and I don’t know that thing about them until they tell me with their mouths. Does that make sense? That’s how I feel after I published a book. But I also feel profoundly lucky to have published that book. And I feel like outside my experience with people who’ve read the book—their experience with me, rather—I feel really excited that I’ve been able to bring my sister into their lives in a way that they can meet her, because they wouldn’t be able to do that now. That’s sort of lasting and interesting to me in a way that my personal life I just don’t care about.

What’s something you’ve read this summer that you’ve enjoyed? Did you have time to read this summer?

I finished The Argonauts [by Maggie Nelson] right before the summer started, before we moved, and I loved it. It’s one of the best books I’ve ever read, hands down. It’s amazing. It’s startlingly good. [Sidenote: It’s on Christa’s CNF required reading list this semester.] And I’ve been reading a lot of essays at this point, in preparation for an essay that I’m writing now, that I’m almost finished with, and for teaching as well.

When you’re teaching, memoirs vs. essays—are those different writing strategies?

One of them is like a sprint, and one of them is like a marathon. One thing that’s good in a workshop is to be able to—whether or not you think it’s going to go into a full length book or whether it’s going to remain in an essay—that each piece that you hand in has to have a life of its own and be contained. It helps you be a better writer. So I had done that when I had started writing Her. I had started to write 20–25 page chapters that really could exist by themselves someplace else. It was helpful in terms of thinking about narrative strategy and how to move from the beginning of something to the end of something and to keep an idea going through the whole piece. It taught me to be a better writer thinking about it that way. I did, once I was ready to think about publishing the book, have to pull it apart again so that there were pauses and that everything didn’t seem so neat and cleaned up at the end of every chapter. Some chapters merged, some chapters split into three different chapters, and pieces were moved. If I hadn’t done it that way, it would have been almost impossible to finish the book, I think. Because I really did it pretty quickly. I started it in the fall of 2009, and my last edits were into my publisher in October of 2012. So it was fast. It was a total obsession. It was just my favorite person, really.

Who is an author or book that you recommend to aspiring writers? Why? How was it influential in your own writing?

(Whispers: Don’t ask me that!) Oh my god. Well, there are so many. I love Robert Creeley. Reading Robert Creeley when I was undergraduate in college at Bard changed my life because I could see the way a punctuation changed a sentence or changed the meaning of everything or how a pause could change the meaning of everything. I still go back to Creeley’s poems now. They don’t really help me write creative nonfiction, but as a student of writing, they were really important to me.

Joan Didion is probably the writer who is most important to me. Play it as it Lays, The White Album, The Year of Magical Thinking, and Blue Nights are stunning. Whenever I’m lost, I will go back to Didion because she has this matter-of-fact frankness that will get you through. She doesn’t dally. One of my weaknesses as a writer is that I’ll kind of allow myself to go a little bit too long in my prose. It’s a good reminder that the short sentence that has an economy to it is sometimes the best way to go, and you just have to keep moving straight ahead. So, Didion always.

Also, John Cheever. The Collected Stories of John Cheever are really important to me for that exact reason. He has these situations that have nothing to do with my life, but he’s able to move through a scene in a really sort of, in a quick way, but then wind in this really long, beautiful sentence out of nowhere that kind of punches you in the gut. I think I want to go for that.

One last one, and it’s very serious: Simon & Garfunkel or Hall & Oates?

Simon & Garfunkel. Right?

2015 Commencement

On the morning of Sunday, May 17, five of our eight graduating MFAs participated in the Eberly College of Arts and Sciences Doctoral and Master’s Commencement.

After three years of hard work, the elation over their accomplishment is evident.

From left to right: John Bryant, Mari Casey, Jessica Guzman, Xin Tian Koh, Morgan Lipkin

MFA Director and poet Mary Ann Samyn, with three of the graudated poets, Jessica Guzman, Xin Tian Koh, and Morgan Lipkin

We send a hearty congratulations out to all of our 2015 MFA graduates:

John Bryant, Fiction

Mari Casey, Fiction

Jessica Guzman, Poetry

Xin Tian Koh, Poetry

Morgan Lipkin, Poetry

Patric Nuttal, Poetry

Sadie Shorr-Parks, Nonfiction

Joanna St. Germain, Fiction

Thank you for your time with us. We look forward to your writing to come!

MFA Hooding Ceremony 2015

From left to right: Xin Tian, JoAnna, Sadie, Patric, Morgan, Mari, Jessica, John

Photo courtesy of Melissa Ferrone

On Thursday, April 30, the Department of English presented all of our graduating MFAs at the annual hooding ceremony in the Rhododendron Room of the WVU Mountainlair.

To begin the evening, Mary Ann Samyn, Director of the the Creative Writing Program, gave an introduction reminding us why we choose to spend three years earning this degree:

“The MFA is an interesting degree. Often we worry over it; we wonder about its utility. We know that as a credential, it is just the beginning. And yet, the time is a gift, we say. And the experience of the community also. And beyond all that, the act of writing, of making our lives available to others is no small thing. We make literature for the same reason we read it and reread it: It’s meaningful to do so. Time well spent. A pleasure, a heartache, a moment of humor or recognition, all of these are worthwhile.”

After receiving proud introductions and the hoods from their thesis directors, graduating students gave short readings from their theses. You can listen to a podcast of the hour-long ceremony on the Center for Literary Computing’s page for Creative Readings: http://literarycomputing.wvu.edu/projects/creative-readings-podcast

To see more photos of the event, visit our Tumblr: http://wvumfaprogram.tumblr.com/: http://wvumfaprogram.tumblr.com/

Please join us in congratulating our eight graduating MFAs:

Patric Nuttall (St. Helen, MI), Poetry

Thesis: A Census of Ghosts

Thesis Director: Jim Harms

JoAnna St. Germain (Oakland, ME), Fiction

Thesis: Lost Nation

Thesis Director: Mark Brazaitis

Xin Tian Koh (Singapore), Poetry

Thesis: I Haven’t Once Forgotten

Thesis Director: Mary Ann Samyn

Mari Casey (Point Pleasant, WV), Fiction

Thesis: Trent and Posie

Thesis Director: Mark Brazaitis

Morgan Lipkin (Camarillo, CA), Poetry

Thesis: Eating a Chicken’s Heart

Thesis Director: Mary Ann Samyn

Sadie Shorr-Parks (Philadelphia, PA), Nonfiction

Thesis: About Face

Thesis Director: Kevin Oderman

Jessica Guzman (Port Charlotte, FL), Poetry

Thesis: Adelante

Thesis Director: Mary Ann Samyn

John Bryant (Collierville, TN), Fiction

Thesis: If They Are Holy They Are Pinned to it like a Spear through a Boar

Thesis Director: Glenn Taylor

Poet James Longenbach Visits Colson Hall

James Longenbach reading

Poet James Longenbach is no stranger to WVU MFA candidates. In the past three years, MFA poets have studied four of his books: the critical prose of The Art of the Poetic Line, The Virtues of Poetry, and The Resistance to Poetry, and the poems in his collection The Iron Key. The opportunity to meet the person behind these texts was cause for excitement. As third-year MFA Patric Nuttall said, “It was great to meet the author of these books we’ve been reading and discussing the last few semesters.” And Longenbach truly rose to the occasion with his visit to Colson Hall.

On April 16th, the day-long festivities began with an afternoon lecture on the lyric poem. Titled “Lyric Knowledge,” Longenbach discussed how form and syntax uphold and subvert expectations to create a pleasurable reading experience. His talk not only considered why we are gratified by familiar patterns, but why we feel we will be relieved by unfamiliar patterns. “We re-read and re-listen,” Jim said, “because of structure, not information.” As evidence for his argument, Longenbach presented various lyric poems with their lines reversed. Read as originally intended, the sun in Wallace Stevens’ “No Possum, No Sop, No Taters” feels like a familiar hope. Read reversed, it becomes a wish or a dream. Asking the audience to experience poems like Stevens’ this new way reinforced the vitality of their original structures.

Mary Ann Samyn and James Longenbach

After the lecture, Longenbach visited the graduate poetry workshop. He fielded questions from the MFA poets about writing, reading, teaching, and what he does in his downtime. “I cannot will myself to write a poem, but I can will myself to write prose,” he said, when asked about his writing processes. But for Longenbach, writing prose is not unlike writing poetry. “We read critics because their essays are beautiful things.” He distinguished reading from writing further, as he said, “Your own poems, you write them to get rid of them. You read what you want to keep. You write what you want to throw away.” Perhaps the most important piece of advice Longenbach imparted was on patience. “Do anything you can do to make yourself not be impatient,” he advised. “Be less anxious.” For himself, being less anxious involves activities outside the literary world, such as learning the lute and watching bad television. But when it’s time for poetry, Longenbach approaches with rigor. He emphasized, “I do not know any poet of achievement that does not think so rigorously about poetry.”

For dinner, Longenbach joined MFA poets and faculty for dinner at Black Bear Burritos downtown, where we all chatted more about our lives and bad T.V. shows. First-year MFA Sarah Munroe said, “We’ve read so many of his books in poetry workshops, it was great to be able to see him in the flesh and hear him speak. When he answered questions in workshop he told us that we’re all servants of poetry, of the poets who will be remembered, if this is the work we choose. A humbling but helpful reminder. It’s also nice to know that someone as well read as he is has guilty T.V. pleasures too, like Gossip Girl.”

Graduate students and faculty with James Longenbach at Black Bear

The night concluded with a reading in the downtown library’s Robinson Reading Room. Longenbach read poems from his forthcoming book Earthling, titled for the archaic definition: one who works the earth. The poems ranged in subject from horse rides, to losing a dog, and a crocodile’s perspective.

April 16th was a full and fulfilling day. Like his writing, James Longenbach gave us much to remember and much to keep.

James Longenbach is a poet and a critic whose most recent collection of poems, The Iron Key, is a meditation on the conditions and consequences of beauty. One of his recent critical works, The Art of the Poetic Line, is an account of the work of lineation in free-verse, syllabic, and metered poetry (ranging from Shakespeare to Ashbery). He has also written widely about modern and postmodern poetry, sometimes emphasizing the historicity of poetic language (Wallace Stevens: The Plain Sense of Things) but also exploring the ways in which poems resist their historical situation (The Resistance to Poetry).

Feed

Feed