An Interview with Alumna Sara Pritchard on her Latest Collection of Short Stories

by Rebecca Doverspike

Sara and her dog Fay watching an episode of “Lassie” on youtube.

Sara Pritchard’s third book, Help Wanted: Female, is a collection of linked short stories set in Morgantown, WV. Each story contains such memorable characters and wonderfully quick movement— turns, momentum— like a dance. In this work, the imaginative and funny mixes with melancholy and deep truths. I had the good fortune to have a layered interview with Sara Pritchard. I asked her questions via email and then we met up at the Blue Moose to converse in person.

Over coffee, we talked about Morgantown and Sara told me how, in 1971, there were two grocery stores on either side of the South High Street Bridge. “I think there’s something to be said for knowing a place closely over time,” I said. And as I continued, ”...even if it’s sad,” she said, ”...yes, but it’s sad.” The word “sad” chimed in the air for a second, overlapping. “So we do sort of hold memory of a place,” I thought aloud, “if not for you telling me about those stores, I wouldn’t ever have known they’d been there.”

We talked about the problem of homelessness. Or rather, mentioned it and quieted, maybe not knowing what to say beyond acknowledging that it’s a real problem.

We spent a great deal of time talking about time and how it works in writing. “Every story begins in media res. So why not move around? If it were not for vignettes, I wouldn’t be writing. White space. Jump cuts. When you start feeling like you have to fill in all the blanks, and explain everything, and you’re just dragging your narrative around, then you’re in trouble,” Sara said. “If you’re paying attention to how we’re talking, we’re all over the place—1971, film, schematics, the audio book—we think in vignettes, fragments; we don’t think chronologically.” In that way, it’s important for a story to find relationships and patterns and not let time tell the story.

“Vignettes are better visually, too,” she said. “It’s arrogant not to break up text for a reader. Like it’s so important that you can’t break it into paragraphs? It’s like someone talking non-stop. Typesetting is important,” she laughed.

At times, we spoke about the characters in Sara’s stories as if they were real people. At times, some part of me related to one of the characters, even when that character’s behavior wasn’t favorable. “I can understand wanting to just sit in a chair in a basement sometimes,” I admitted, and Sara told me how much she loves quiet. Part of what good literature does is help us understand, or be understanding toward, people who we might otherwise dismiss when we’re unable to see their interior(s). Sara’s stories show how interior lives respond to the strange and difficult things that happen in life, and gives pause to hasty judgment. In fact, her writing gives pause to interpretations that don’t have love in them, even when that love comes in the form of heartbreak. With the story “Friends Seen and Unseen,” Sara was thinking of Susan Smith, and wondering how someone could do such a thing. The process from asking one’s self that question and writing to think through it, to imagine possibilities, to take pen to page and illumine, is one of empathy, I feel. Kim Bennett’s Review speaks well to this aspect of Sara’s writing.

Speaking of internal lives, Sara told me how much she loves being married to a writer (Kevin Oderman). “We understand one another,” she said, “we both have big, big, big interior lives.” I thought that was beautiful, and a reminder that one needs space for one’s interior life in order to bring worlds and words to the page in the way(s) that she does.

“You really brought these characters to life,” I said. “The world felt more alive after I read this book. I’m walking around in a different world.” These stories condense life and make it feel charged, and yes, set aglow.

In the middle of one of my questions or comments, Sara began to respond and then paused to say, “I should say that I don’t know anything about writing. I’m talking about it, but I don’t know what I’m doing.” I loved how she said this because I often feel admitting not knowing strengthens credibility. She’s a writer, and so much of writing involves not having words, not knowing, seeking, attempting. Writing’s a beautiful kind of active not knowing; there’s nothing lazy or passive about it—writers aren’t stepping away from the world so much as translating from the center of it. I loved how her comment related to the way writing begins for her—from something she doesn’t have words for.

Sara has a glowing and contagious laugh, and it brightened our conversation at every turn. Melancholy was present, too; these things entwine. I often think of something Khalil Gibran wrote: that one’s capacity for sorrow is also one’s capacity for joy. Sara’s capacity for experiencing life is deep and in reading her writing, readers’ capacities deepen, too.

Please enjoy our email transcript below, which include Sara’s thoughts on the unconventional, mythology of place, her characters, current reading, and more. Then, go read the book, or listen to the audio book! (Click here to listen to a preview of the audio book and really lovely radio interviews). I hope, and suspect, you’ll find as much pleasure in reading her responses as I did in being able to converse with her. Thank you, Sara.

R.D.: I feel like the “heart” of these stories comes at interesting moments/places timing-wise. Of course, there’s heart (revealing, opening) all throughout, but I’m thinking about the places that that revealing/opening widens, and how you sculpt those moments structurally. I’m thinking of the paragraph in “A Forever Home,” where Ponce de León ruminates on feigning sleep and staying with Billy so that Clara doesn’t have to make a difficult decision—my heart just sunk some reading that. And, in, “The Jaws of Life,” heart is revealed throughout the story, but really comes together when the women talk over wine and Abigail confesses a secret to Sissy. In “Friends Seen and Unseen,” there’s that chilling scene at the end, built up so rhythmically. In “Two Studies in Entropy,” the structure feels parallel, layered. I think the question in here is: do you feel the shape of a story before you write it, or does it form while writing? How do you get a feel for the shape of the story?

S.P.: Such an interesting question, Rebecca. I think every story takes its own form. I suppose some writers (any genre) have a structure in mind when they begin, maybe a form that’s been kind of calling to them, like a braided narrative or an epistolary form, or say, a formal structure like a sonnet or villanelle, which is definitely going to play a big part in what is said, what is revealed—how, when, and where—and certainly determine where and when what you call the heart of the piece “opens”. I have no idea of the “shape” of a story before I start writing. I’m working from images and fragments and, mostly, feeling. Feeling and voice. I’m beginning with voice and a strong sense of wanting to convey something that’s still rather vague to me. Usually, it has something to do with heartbreak, something I don’t really have the words for but damn if I’m not going to try to express it. Somehow. Not until I hear the narrator’s voice can I begin. There’s something, some sense of something that I want to get across, something deeper than narrative. Narrative is the access ramp. To me, narrative/plot is actually the least important element. I don’t really care what happens in a story, only what’s left after everything has happened and the story’s over. The structure just evolves along the way.

I just finished reading Sarah Beth Childers’ wonderful Shake Terribly the Earth, a book of personal essays, and I loved the way Sarah Beth uses the word ‘yarn’ as a verb. I’d never really heard it used that way. She speaks of her grandfather and uncle ‘yarning’ in the next room. Of course, we’ve all heard the word ‘yarn’ used as a noun, synonymous with ‘tale’, but as a verb I find it a particularly precise word for the process of storytelling. It’s as if you have this thing, this thing you want to tell, and it is very real, very much like a ball of yarn, and you begin feeling it, getting a sense of its properties (the texture and elasticity and gauge) and its potential (what you can make out of it) and then you begin to work with it, unravel it a bit and work a couple of rounds, and something begins to take shape. An idea of what it could be. A pattern emerges. Strands. Motifs. Reindeer. (Can you tell that I’ve been knitting a lot lately?)

R.D.: In each of these stories, I love how the writing, and subsequently readers’ attention, moves from detailed focus on a character—description, dialogue, scene—to a wider perspective of what surrounds (weather, insects, birds, the morning paper, etc.). The story holds time in a larger way, then, too, as we can sense it moving—the world moving around the world of the story/characters. How do you balance this focusing-in-on and drawing back? How can you tell when stepping away from the characters to the larger world for a moment would be beneficial/crucial to the story?

S.P.: Hmm. Another interesting question. I think manipulating distance—and time—is important in stories, just like it is in film. We’ve all seen those podcasts or webcasts or whatever they’re called where somebody is giving a reading and somebody from AV/IT comes in and sets up a video camera on a tripod, points it at the speaker, gets it started, and then leaves. They’re horrible! Point-of-view is like camerawork. Long shots and close-ups and jump cuts, and panning. I don’t know the film terminology, but I know that the narrator is holding the camera. The narrator has to vary the distance, look around, look out the window, look in a mirror, pass the camera around to some of the characters. That kind of thing. It’s not something conscious. It’s just a natural way of writing and telling a story. If you don’t do this, then you end up with navel gazing or the podcast-type thing I mentioned above. The same thing with time. You can’t just write in the present tense. It’s boring. Time is fluid and jumpy.

My own tendency is to move away from what’s happening whenever I’m getting too close to something painful or “hot.” When there’s too much tension or conflict. It’s like holding your hand over an open flame. You can’t do it for very long. And in those instances, I often revert to something that will provide a brief reprieve in the form of comic relief, say just an image, just an image that captures something about the absurdity in the moment. Or a jump cut to something near or far. And moving about like this also has a lot to do with pacing. I know I digress a lot—probably too much—but it’s the only way I know to slow things down, draw out the story, deepen it. Well, you can do that with white space, too.

R.D..: One description of this book (and perhaps you wrote it!) states, “Ten interrelated stories set in the mythical town of Morgantown, West Virginia, over a thirty-year period.” I so love that phrase, “mythical town of Morgantown.” It reminds me a little of Italo Calvino’s Invisible Cities;imaginative descriptions of several different places that all wind up being angles into Venice. Do you find Morgantown mythical? How is a place/home (or how can it be) mythical to you, and how is it mythical, do you think, in these stories?

S.P..: Nope, I didn’t write that description. Probably an Etruscan Press intern did. I do think the word ‘mythical’ is great. Everyone has their own mythologies. Every place is a composite of the mythologies of the people and animals—some would say stones, even—that know and have known it. “My Morgantown,” is mine alone. “Your Morgantown” is uniquely yours. My dogs know all the smells in the graveyard; I know the names on the tombstones. Somebody else knows Morgantown’s bars, the buses, the benches. Katie Fallon knows the birds. Everyone’s Morgantown is different, made up of their experiences, their stories of place. But they intersect and merge. And this is the spirit of place. A place is not just physical; it’s full of relationships and associations and memories, everything played out and layered in time. Like I sometimes lie in bed at night in this house that was built around 1920 and wonder who else has lain awake in this room, this very corner. Or the antique beds you see—beds in which babies were born and others died. Everything, every place, the land itself, I think, is imbued with—charged with—feelings and stories, and as you say, mythologies.

R.D..: Each of these stories left such an impression on me. I didn’t want any of them to end; I got so into their worlds (though they did not feel incomplete). The linking is interesting that way, because when a character recurs—Prophet Zero, Jamie—it brings a familiar warmth, and a wonder. Did you mean for this interweaving to mirror life in some way? How do you feel about the stories’ linkage in terms of time? I think you capture the way things (and people) come and go (“Personal Effects” speaks to this well?). Perhaps in this way, Morgantown itself is a kind of character that “stays” (just like a couple of the houses you provide history of and then show their present-of-the-story frat boy inhabitants?). It occurs to me that the reader becomes a kind of place, like Morgantown, because of the ways these presences and stories stay with me after I finish reading.

S.P..: Linked stories seem to me to be the natural form of storytelling. The form is as old as the hills, so to speak. The Iliad and The Odyssey. Epic poems but linked stories, also. The oral tradition is full of recurring gods and monsters and heroes. Life is a series of linked stories. History is a series of linked stories. Sort of like that six degrees of separation thing. We’re all connected in some way. Help Wanted connects some of the dots in Morgantown. And, yes, I do think that place is as significant as a character in any story. Morgantown is, yes, the major link in Help Wanted. It’s the stage, but it’s much more than that. And, if you live here or have lived here, then naturally you can participate more in the stories. You’re an observer but a more knowledgeable one than the reader who is removed, who has never been here. You might even take a second look at Family Dollar on High Street as you drive by. Or the old Dairy Queen. My hope is that the depiction of Morgantown is specific enough to add another dimension for some readers, but general enough to be representative for others.

R.D..: The “Cottonwoods,” a homeless camp by the river, recur, too. What do you think about the Cottonwoods and that place’s relationship to Morgantown?

S.P..: Well, I think I made up that name “Cottonwoods,” but I know for a fact that there have been homeless camps along the railroad tracks here for years, one big one below the arboretum. I knew people who came upon them, one person who lived in one of them back in the 1970s. I knew some people who lived at Lock 11, in the old lockmaster’s house along the railroad tracks. And under the South High Street Bridge, too. There have always been people basically living under there. Look down along Decker’s Creek when you walk across the bridge. I’ve walked over it for thirty years. Homelessness is a real problem, not just in Morgantown, but most cities in America. And it’s not addressed. A city gets a bike trail, a farmer’s market, a couple of Starbucks and two 20-screen stadium-seating theaters showing the same five crappy movies in regular and 3-D and BINGO! Best Small City in America!!

R.D..: Are some of these characters “real”? What compelled you/drew you to write about them?

S.P..: Ah, the questions everybody wants to ask! Is it true? Is that me? Did that really happen? Did you really wear a rabbit costume to work? What about that carrot? Folks: it’s fiction! Well, as Alice Munro said of her stories, “There’s always a starting place in reality.” And that’s the truth. But how much is true? Some. Not much. What compels me to turn real people and events into characters and scenes is that those people and events interest me, that I find them compelling and perplexing and worthy of story. And because I have been affected by them. And probably, too, because I’m really not that creative when it comes to making up stories, so I always start with what I know. But I just let my imagination run wild. It’s fiction, and I make no apologies. If I start apologizing, I’ll never end.

R.D..: Empathy pours through these stories. In, “What’s Left of the Jaime Archer Band,” one couldn’t help but feel drawn to the man who claimed he was from another planet as compared to the comparably “dull” marriage and life Nina had following (and plus, he was so charming, playing the oven rack as an instrument!). Do you wish people lived with more imagination in a way that didn’t dismiss things as “crazy”?

S.P..: I guess I have always been bored by the conventional, attracted to the unconventional and odd. I think if everybody played the oven rack, the world would be a better place. Try it!

R.D..: I read these stories while I was away from Morgantown, and I loved how they made me “homesick” for the place. What are your feelings about Morgantown?

S.P..: Morgantown has been my home for nearly forty years, and I’m really sorry to say that I think it’s really gone downhill. Maybe I’m just nostalgia ridden. I would need my soapbox to explain this, but I’ll just say that there’s no real vision for a sustainable downtown (what? another Sheetz?), for community. A sister city in China? How about one in Vermont instead—like Middlebury, VT? Urban deer hunting? Marcellus gas drilling? Ask me about the new traffic circle, the new “green” school, the apartments on West Run, the County Commission, the TRAFFIC! Ask me who owns WVU! O.K. I better shut up. Or as Kevin always says to me: “Start a blog!”

R.D..: My favorite blurb on the back of your book is: “Sara Pritchard sees everything. . . and looks at it with such tenderness, clarity, and good humor that all of it begins to glow.” I agree. Where does this vision come from? (An impossible question, I know? maybe it’s: how do you cultivate such clarity, understanding, and empathy toward this world? Or maybe, how do you recommend others do so? Maybe by things like reading your book…). I laughed a lot while reading, but with tenderness—such a compelling combination. Thank you.

S.P..: Thank you, Rebecca.

R.D..: When did you start writing?

S.P.: I was a closet writer for many years. And, really, I didn’t start writing stories until I got a computer, until I learned how to cut and paste. That’s the truth. The late ‘80s, early ‘90s.

R.D..: Do you think the writing itself, working with language, contributes to the kind of vision Rebecca Barry aptly describes, or do you see writing as a way to express that vision? (These people and dogs are often loveable, but I think it’s very much the tone itself that makes them so. You absolutely do bring them to life.)

S.P.: I think it’s art—writing, painting, photography, music, etc.—that makes things glow. (O.K. well, love can make everything glow, too.) I mean, yeah, they glow in themselves, but making something permanent of them—to me, that’s with language and finding the right words to describe something, finding the right image or metaphor—that makes that glow stick.

R.D..: There’s such playfulness in these stories. Always the playfulness gestures towards and touches deeper truth (like a beautiful critique of things such things as capitalist society—at least I see that!), but I love the playfulness. It seems at times almost like playfulness is a kind of survival strategy (I’m thinking of “Help Wanted: Female, Part I”). Perhaps this is related to my question about imagination, but I see some of these stories as a plea for playfulness, or an in-defense-of (except for scenes like Tripkin and maybe even Marcie’s mother? there, it seems like imagination does dip too far in such a way that makes things difficult rather than bearable. An interesting distinction? perhaps we can talk about that). I don’t mean frivolous play (is there such a thing, really?), but rather stepping outside the rigidity of rules which are founded on such ludicrous and inhumane premises. Can you comment on the existence of playfulness in your life and/or in these stories?

S.P.: I like your term “survival strategy.” That’s it, exactly. Gravity and Levitas. We need both to stay alive. And back to comic relief. For me, comic relief is my—as you young people say—”go to.” Any story that is relying on a punch line is never going to work. That kind of calculation and movement never works. But underneath everything that appears to be funny is always something sad or tragic. Terrifying, even.

R.D..: Do you have a favorite story in this collection?

S.P.: Maybe “A Forever Home,” because it’s really kind of a love letter to my nephew Billy, who I knew when he was a little boy, who loved dogs, and who died in 2008. I also like “The Man in the Woods.”

R.D..: Were any of the stories hard for you to leave, as a writer?

S.P.: Well, yes, that story “A Forever Home.” I knew it was sappy, and I resisted writing it for a long time, but it kept whispering to me.

R.D..: Can you describe a difficult moment in your writing process and how you overcame it?

S.P.: The most difficult moments are beginning. I really don’t like to write. I’d rather read. Kevin (husband) said once to me, “You know, I don’t really like writing. I like having written.” I find that to be true. I don’t like sitting and typing. I love it when I finish something and then I can go lie down.

R.D..: Who have you been reading lately?

S.P.: In the past two weeks, I’ve read volumes one and two of the Norwegian writer Karl Ove Knausgaard’s six-volume, 2,500+-word novel, My Struggle, translated by Don Bartlett. And I reread Sleepless Nights by Elizabeth Hardwick. I read Hardwick years ago (1980s) and didn’t realize how avant garde Sleepless Nights was for a “novel.” The 2001 edition has a very interesting introduction by Geoffrey O’Brien. These novels interest me because they’re rather genre busting. All three of these books are novels without plots, with narrators/protagonists with the same name as the author, and with circumstances that mirror the lives of the authors. Knausgaard’s and Hardwick’s books, though, are very different. Knausgaard’s is something like the literary equivalent of reality T.V. He admits to being very influenced by Proust, and the story he’s telling is so utterly mundane that it should be utterly boring, but . . . for some weird reason, it’s compelling. I mean, it’s a page-turner. Anyway, I’m very interested in this form of writing: fiction and memoir that doesn’t apologize for itself, that admits to untruths—and truths—but without explanation. I think it’s about time that a form like this rose up out of the mire of memoir and autobiographical novels. I’ve always been annoyed by the fact that prose writers are the only artists who are continually asked, Is that true? That we have to sign up for one of two camps: fiction or nonfiction. Oh, and then there’s creative nonfiction, a genre defined by what it’s not??? What’s the matter with the term ‘essay’? Do we ask poets or painters or songwriters or playwrights that question? But, is it true? Maybe it’s the fifth genre, sort of an unapologetic memoir with improvements. Tim O’Brien does the same thing pretty much in The Things They Carried, writing in a character named Tim O’Brien and using the same material he first wrote as memoir (If I Die in a Combat Zone, Box Me Up and Ship Me Home). And I love the foreword to Alice Munro’s story collection The View from Castle Rock. She says:

You could say that such stories pay more attention to the truth of life than fiction usually does. But not enough to swear on. And the part of this book that might be called family history has expanded into fiction, but always within the outline of a true narrative. With these developments the two streams came close enough together that they seemed to me meant to flow in one channel, as they do in this book.

R.D..: What’s next for you, project wise?

S.P.: I don’t know. What’s next for you, after your MFA?

R.D.: I don’t know.

Good thing not knowing can be a place to start, too.

Sara Pritchard is the author of the novel-in-stories, Crackpots, which won the Bakeless Prize for Fiction and was a New York Times Notable Book of the Year, and the linked-story collection, Lately. Her new story collection, Help Wanted: Female, was published by Etruscan Press in July 2013.

Sara “grew up” (ha ha ha!) in Northeastern Pennsylvania (Hazleton/Wilkes-Barre area); Rochester, New York; Denville, New Jersey; and Ocracoke, North Caroline, but has lived in West Virginia for a really long time (somewhere between 35 and 40 years, give or take a few years). Her stories and essays have been published in literary magazines including New Letters, Green Mountains Review, Northwest Review, Tusculum Review, Spittoon, and elsewhere. She teaches in the Wilkes Low-Residency Creative Writing Program and lives in Morgantown, West Virginia, with her husband, author Kevin Oderman, and their dogs, Fay and Figgy (aka, Brownie).

Contact Sara at pritchard.sara@gmail.com.

The Council of Writer's Fall Formal Reading

by Rebecca Doverspike

True to tradition, the weather provided a blustering cold backdrop for the Council of Writer’s Fall Formal Reading on Friday, December 6th. As MFAs, literature students, friends, and faculty gathered in Colson 130, I had the sense that we filled the room, but quietly—a fullness of presence, ready to listen.

We gave this reading a comic book theme, revealing each reader’s inherent superpower. Third year fiction writer Nathan Holmes put together this utterly fantastic program that illustrates not only superhero names but also a narrative itself (amazing, Nathan!). Click here to fill your eyes with imaginative wonder. And hey, only $0.10 a copy.

Troy Copeland, a third year nonfiction author, MC’d this event, introducing each reader with a tone that combined mysticism and earthiness (not unlike his own writing). And so, before any of us even stepped up to the podium to share our words, we were all but adorned in capes, cloaks, and invisible shields. I’m now convinced there’s no other way to give a reading.

From Feagin Jones, swooping in to rescue a last-minute reading switch, the Ursa Warrior (she can shift to bear on command; no moon needed), we heard a biography of her relationship with poetry. We heard about Wordsworth and God and the way poetry spins above but is also close, close enough to touch, and change, one’s very blood.

From Claire Fowler, the Miraculous Moon Mover, we heard from a nonfiction piece titled after an Isaac Asimov short story (“Nightfall”) in which the narrator threads astrology and science through an attentive, undefined116122.undefined116123.undefined116124.undefined116731.undefined213152.documented, experience at a psychiatric hospital. This essay was chosen to represent WVU in the AWP Intro. Competition (yay, Claire!).

Sara Lucas, a featured reader, who can sing her way through anything and play any instrument she touches, read from her novel in which a character, Marcie, bakes something delicious with words sweet enough to make our stomachs grumble and feel the warmth of a lit kitchen somewhere on that cold evening.

Melissa Ferrone, the Wondrous Wave Disruptor, read from her essay, “Linton Hall Elegy,” soon to be published in The Fourth River’s Women & Nature Issue, in which she puts an astounding amount of things in relation to one another—birds, nuns, school girls, drawings, prayers. She even wonders what Christ’s favorite bird was. Who has wondered that before? It felt like one of those questions that seemed at once natural and utterly profound, at once commonplace and yet opening new thoughts to the world.

After a chatty intermission in which we enjoyed some potluck sweets, we began the second half with our second featured reader, poet Christina Seymour (another AWP Intro. Competition representative), who can turn into whatever she touches.

Christina seemed very close to her work. She read about wonder, loneliness, longing (“one cannot marry a river”). She put in one line something I’d tried to write paragraphs about before (that’s what poets do), about being told not to stare into the sun as a child and doing it anyway—the blank spots in vision after. Fireflies flickered in a poem, too, showing us Christina’s vision in all kinds of light.

Next, Sadie Shorr-Parks, who can freeze time! People want to paint her because she can hold so still. She read us a narrative about babysitting her younger brother. Very Sadie, the piece made us laugh and made its way to truth through a quirky and entertaining route. She makes fun of the world, and herself, in such a way that allow truths to surface.

Jacqulyn Wilson, the Unrivaled Roar of Radiance (indeed!) read us beautiful poems. Angels made an appearance in the poems—one time as taking someone into their presence, and another as a speaker’s wish for them to be rattling at the door instead of her neighbor. An image remains of a flower vase the speaker wanted to keep upon a breakup, and a last moment of holding hands before parting. These poems swooped in with importance, much like angels might.

The Impressionable Prism, Hannah McPherson, read from an essay, “Houses: Four Ways,” in which some she articulated the ways some homes are physical structures with walls and others are inside, spiritual. She read to us her perceptions of the relationship between different kinds of houses in Turkey and America, in other people’s lives, and her family’s. It gave us pause to reflect on what’s interior, what’s exterior, and where we situate ourselves within shifting notions (shall we say prisms?) of home.

Our last featured reader, Rebecca Doverspike (me), the Indefatigable (ha) Dazzler read from an essay she wrote her first semester of graduate school but is in the process of revising for her thesis. “First Communion” sees the wafer in Catholic communion as the moon brought to earth, Christ in the form of solidified light that dissolves. This essay speaks to her relationship with her grandmother and Catholicism and writing, too (this is why the structure shifted from chronology to collage, to allow those parts their own space to bloom and relate rather than clutter the reader’s head).

Shaun Turner, the Amazing Atom Splitter, cut through the invisible atoms in the air with his two flash fiction pieces that got right to the core of things. Nothing stills a room like a first sentence in which someone gets shot in the head while sunbathing. And yet, this is the world in which we find ourselves; Shaun showed it to us through characters with clarity. One of Shaun’s stories was chosen to represent WVU’s AWP Intro. Competition). Woot!

There’s a reason I put Troy Copeland, the thundering tempest who can call forth the winds, last on the program: he’s a tough act to follow. He must’ve gathered some of that wind before he began a phenomenal reading from one of his early essays in the program, “Echoes to the Senses.” He read rhythmically, intellectually, and genuinely about words’ role in performance and identity. Troy’s writing is very intellectual, but he never leaves his readers behind—always he considers us, brings us with (“In imagining that, you have entered the gulf with me,” where “that,” is a man of African descent standing knee-deep in the ocean reading aloud from Tennyson. And later, “that,” becomes the knowledge of being one drop of that ocean and also the spaces between). We journeyed with, through his sentences, to find, at the end, a graceful articulation of the space between words, and how we are all connected through that space. I could feel that connection palpably between the people in the room as his reading ended. From one mind’s thoughts and perceptions of being alive to a collective consciousness of that phenomena. It left us grateful.

Thank you to all who came to listen to this reading (so good to fill the room!) and stay tuned for another volume of MFA Reading in the Spring.

Photos of the Featured Readers below are courtesy of Christina Seymour:

Sara Lucas, leaving us hungry for more after reading from her novel.

Christina Seymour, gracing us with her poems.

Rebecca Doverspike, relating her hesitation in sentences with nearly not arriving in the world.

Fall 2013 Bolton Workshop Reading

by Rebecca Doverspike

Funded by Mr. and Mrs. Bolton and coordinated by Mary Ann Samyn, each semester MFA students teach creative writing to undergraduates in the dorms. Once a month, graduate students bring writing activities and prompts to the dormitories and offer enthusiasm and feedback to the writing those activities produce. To read about some of this material, visit the Bolton Workshop blog.

At the end of every semester, there’s a reading free and open to the public, for participants to share their work from the workshop. At this semester’s reading on Sunday, December 8th, while eating Mary Ann’s delicious cupcakes and fresh fruit, we heard each Bolton workshop leader describe their workshops and the students they worked with. We then listened to two brave students read their poetry. And, finally, special guest Jim Harms read from two of his most recent poetry books, After West and Comet Scar.

It was lovely to see such a diverse audience of professors, graduate students (some Bolton workshop leaders and others just there to listen), undergraduates, Resident Faculty Leaders from the dorms, and others. The audience actively listened—when Bolton students read their poems, I noticed several nods and “mm hmm”’s, and a “wow, that’s very good.” I felt glad that such work can reach a variety of ears. We were each there to celebrate writing, all of us in different stages of that pursuit.

Before Jim read us a few poems, he shared the epigram to After West by Walt Whitman: “Long having wander’d since, round the earth having wander’d, / Now I face home again, very pleas’d and joyous, / (But where is what I started for so long ago? / And why is it yet unfound?)” Jim said he feels like all literature is about journeying home and realizing you can never quite get there—that we write to find our way home and simultaneously realize it remains “unfound.” To me, that articulated the writing space quite well. Perhaps it isn’t just about the tension or sorrow in the “unfound,” but rather that the space between home and not comprises its own familiar place that one can become okay with, or maybe even love. As he read, I pictured the way writers exist in that space, somewhere on the edges of a thin blue-lit boundary (am I thinking of the stretch of light where sky meets water, or maybe the way light looks on mountains from a distance, or just a horizon and the way it shifts, daily?), learning the art of translation—translating life.

Photos courtesy of Morgan O’Grady:

Bolton workshop leaders Hannah McPherson and Christina Seymour talk about their semester working with students in Summitt Hall.

Caleb Milne, reading poetry with wonderful pacing, like going for a walk and actually noticing what’s happening, inside and out.

Mitchell Glazier, reading poetry. Christina Seymour says: “his writing is visceral, often offering an electric voice that is full of emotion and tension. You can tell there’s personality behind his writing.”

Poetry guest Jim Harms, reading, and conversing about, poetry.

WVU MFA Program Partners with Preston County Middle School

by Morgan O’Grady

The WVU MFA program has struck up a partnership with Keisha Kibler’s 7th grade classes at West Preston County Middle School to start a Creative Writing Club. We have had two visits so far, where we wrote poems from different perspectives and also worked on Sijo poems (three line poems that have about 14-16 syllables per line). We all had a great time, and we can’t wait to continue this partnership.

I asked a few MFA participants a some questions about their experience:

What were you expecting before arriving at West Preston County Middle School?Feagin Jones: I figured some kids would think poetry was lame and other kids would be really into it.

Travis Mersing: I anticipated working with students with a wide range of experiences and expectations when it comes to poetry.

Shaun Turner: I came into this experience with a pretty open mind. I did expect that the students would have a little trouble trying to describe the world around them.

Morgan O’Grady: Well I had hopes for it to go well, but I also had a bad dream where the lesson just flopped. I wanted all of the students to know we care about being there and we care about their writing.

Why did you volunteer?Feagin Jones: I really started writing when I was in 7th grade. When I was 12, if some people from an MFA program came in and helped me with poetry, I would have thought it was the coolest thing ever.

Travis Mersing: Being from Preston County, I saw it as a chance to go back and work with students with a similar background as I have. Also, I thought it would be both fun and rewarding to help students create, explore, and interact with poetry.

Shaun Turner: I volunteered because I believe in creative writing—more specifically, I wanted to help the students understand how important writing is, and how writing can help define the world around them.

Morgan O’Grady: I volunteered because I, along with Jessica Guzman, wanted to keep the connection with West Preston County Middle School workshop we formed during the spring. It is important to be involved in our community.

What part was the most fun for you?Feagin Jones: I really enjoyed how excited some of them were about the whole thing—how their little eyes lit up when they asked me if they could do this or that, and I responded that they could do anything.

Travis Mersing: Hearing some of the odd, funny, and profound ideas that some of the students came up with for their poems.

Shaun Turner: Interacting with the students was really great. I loved helping them with descriptions by asking them questions. “What does a dragon do?” “What does a sunrise look like?”

Morgan O’Grady: What I look forward to most is seeing how proud many of the students are after they write a poem. Typically, some students feel that they are not good writers. What a myth. We are all writers, and good ones. I have to confess I do enjoy the energy the students bring. We can talk about unicorns, life, death, narwhals, or just the weather. It’s magical.

How were your expectations met or exceeded?Feagin Jones: Some of them did think it was lame and some of them got really excited. When I looked at them, I felt like I understood them. I remembered myself and my friends when I was their age.

Travis Mersing: It was nice to see that all the students that I had a chance to work with were very open to the idea of writing poetry. They were creative, funny, and thoughtful. It was a nice experience.

Shaun Turner: My expectations were exceeded! These students did a great job showing their unique, interesting voices.

Morgan O’Grady: These students have so many great ideas. They are funny. They are serious. They are silly. I was excited to see how receptive they were to writing and how much many of them enjoyed it.

What are your hopes for this in the future?Feagin Jones: I hope we can go once a week forever, and really make this into a thing. I think it’s great for the kids to do this.

Travis Mersing: I think that the continued partnership between WVU and WPMS can be one that will benefit everyone involved. I’d like to see it continue as a way to let middle school students be expressive and creative in the classroom as well as letting them know that there are ways to pursue poetry and the arts beyond the extracurricular status that these pursuits often have.

Shaun Turner: I hope that our WVU MFA community can continue working with the students at West Preston, and I’d love to see more interaction with local schools.

Morgan O’Grady: My hopes are about to bust my ribs. I want to be able to expand into other classes in the school. I would like to go every other week. I would love to work with other schools: elementary and high school. We have the time, we have the people, and we can find some funding. Our program can offer a lot more than an opportunity to enhance our own writing skill by being a part of the public educational community. I might be thinking too large, but I would like to see this expand upwards and outwards.

Below are a few photographs from both days of volunteering:

Travis Mersing, Jessica Guzman, Barrett Lipkin, and Morgan O’Grady pause for a group photo at West Preston County Middle School

Hannah McPherson, professional and stylish, at West Preston County Middle School

Feagin Jones, Jessica Guzman, and Travis Mersing after a day of 7th grade poetry at West Preston County Middle School

Collaborative Letter-Writing Project with Sandy Baldwin and MFAs

Our CollabCreate team (Sandy Baldwin, poet Morgan O’Grady, fiction writer Jessi Lewis, and poet Christina Seymour) created a Kickstarter for their letter-writing project. If you’re feeling supportive, and in-want of a pen pal, watch and click the $ button! Thanks from the team!

http://www.kickstarter.com/projects/528617813/youve-been-contacted-a-mailing-project

Calliope

by Rebecca Doverspike

WVU’s lovely undergraduate literary journal, Calliope, is now accepting submissions. The journal is student-run and publishes WVU undergraduate work exclusively. Calliope has a long standing history at WVU and has twice won the prestigious AWP Award for Design. Indeed, whenever I see copies of Calliope in Colson Hall’s Main Office, they catch my eye. The shape of the journal shifts a bit from year to year and its various incarnations are alluring; I often find myself paging through the journal while I’m talking with a secretary, passing through to use the copy machine, etc. In recent Issues, I recognize many of the contributor’s names, as those students went on to MFA programs (sometimes right here at WVU) and to accrue more writing publications. Students who work on the journal, in the capacity of an Editor or reader, also have a history of going on to graduate programs. Two-time Editor-in-Chief Natalie Caprini, for instance, is now a PWE graduate student here at WVU.

Here is the journal’s current masthead, overseen by Director of Creative Writing, Mary Ann Samyn.

Caleb Stacy: Editor-in-Chief

Celeste Lantz: Managing Editor

Nathan Ward: Art Editor

Hope Hart: Fiction Co-Editor

Maggie Kinder: Fiction Co-Editor

Tori Dobbs: Poetry Editor

Janelle Vickers: Nonfiction Editor

There are still opportunities for more undergraduate journal readers as well. Anyone interested should can get in contact with Editor-in-Chief Caleb Stacy at: wvucalliope@gmail.com. Caleb articulated the importance of student involvement with Calliope: “One reason I think it’s important to get involved in this kind of role is because of the unique experience it presents for young readers and writers and prospective graduate students. While there isn’t a major requirement for any of our positions (e.g., an engineering major could be an editor), a journal-reader or editorial position would look great on any resume or CV. These positions reflect a person who can work under deadlines, someone who is able to form opinions about several pieces of writing, and someone who is able to work with an overarching goal in mind. I’d encourage anyone with plans for some type of graduate study to consider getting involved with Calliope. It’s a great opportunity to learn and practice skills that are useful in both an academic and professional setting.”

We look forward to the next publication of Calliope and wish all the editors and readers well as they embark on the process to select student work for publication.

To read more about the journal and the submission process, visit here.

A Tribute to Poet Tom Andrews at the Second Annual Department of English Gathering

by Xin Tian Koh

Usually empty on Friday evenings, Colson Hall brimmed with guests, faculty, and students on November 1st, 2013, for the second annual Department of English Gathering, which was part of West Virginia University’s Mountaineer Week. Not too far away from a wine and hors d’oeuvre reception, we hosted a display of MFA work in Colson 223, presenting how we workshop each other’s work and collate our revised works into a thesis. The MA, PWE and PhD programs, the Center for Literary Computing , the WVU Writing Center and the Appalachian Prison Book Project also shared their recent accomplishments and student projects with guests, and secretary Cindy Ulrich’s Powerpoint presentation of department, faculty, and student projects made “everyone look like a rock star,” in Rebecca Doverspike’s words.

The evening culminated in a tribute to poet Tom Andrews. A friend of the WVU English Department and MFA program, Andrews grew up in Charleston, West Virginia. He studied at Hope College, Oberlin College, and the University of Virginia, taught at Ohio University and Purdue University, and was a Poetry Fellow at the American Academy in Rome. Andrews’ publications include poetry collections The Brother’s Country and The Hemophiliac’s Motorcycle, and the memoir Codeine Diary: True Confessions of a Reckless Hemophiliac. Andrews died in London in July 2001, and professor Jim Harms opened the tribute by noting how Andrews left behind “a remarkable body of work” and that “it’s our job to celebrate it.”

MFA graduate Charity Gingerich and MFA students Rebecca Doverspike, Christina Seymour, and Hannah McPherson presented English Department guests, faculty, and students with a round-robin reading of Tom Andrews’ poems “The Hemophiliac’s Motorcycle,” “Evening Song,” and “Hymning the Kanawha” from a collection of Andrews’ work, Random Symmetries. We were joined by writer and translator, David Young—retired professor of English at Oberlin College, editor at Oberlin Press, and co-founder of literary journal FIELD, where Andrews had been an intern. David told us how Andrews, who was more like a colleague than a student to him, loved “being a writer, being among writers,” and how he admired Andrews’ dexterity with endings in his poems.

Creative Writing Program Director Mary Ann Samyn shared a personal reflection on Andrews’ life and ended the evening by reading his poems (which she described as “what poignancy is”): “At Burt Lake” and “North of the Future,” Andrews’ last completed poem. The English Department is thankful to Alice and Ray Andrews for their support of this event, and the WVU Libraries will soon be receiving the Andrews family’s donation of Tom Andrews’ personal papers into its collection. West Virginia University is honored to be part of his literary legacy.

Beverly Donofrio Reading

by Melissa Ferrone

The air in the Robinson Reading Room was magnetic when Beverly Donofrio began her reading last Thursday, October 17th. She began by discussing the tragic inspirations behind each memoir—the thing that pushed her to write, to discover, and to cherish. Her first memoir, Riding in Cars with Boys, was inspired by her turbulent upbringing and the challenges she faced as a teen mother. After the memoir and film-adaptation were released, she commented that she still did not feel fulfilled: “I had been given everything I ever dreamed of, and I still wasn’t happy.” In looking for happiness, she discovered the rich and fantastical history of the Virgin Mary which led to her second memoir, Looking for Mary. Most of her reading on Thursday revolved around her most recent memoir, Astonished, a gritty and hopeful book about surviving rape through faith and rediscovering one’s self.

To say that the audience was enthralled would be an understatement. The audience was mesmerized as Beverly read, as she talked to us like we all just sat down for dinner in her home. Beverly pulled us into her life through great swells of poetic moments and detailed language. Truth, faith, and the beauty and brutality of life comprise the vital center of her writing.

A palpable desire to know and understand Beverly was vividly evident when the audience began asking her questions. This was the first reading I ever attended where questions went on for thirty minutes. Some questions focused on her writing process, while others revolved around her relationship with God.

One student asked, “What would you tell someone who is going through a tragedy right now?” Beverly responded, “I’m not sure how to answer that. Just know that regardless, whatever comes out of the tragedy will be good. It will give you something good. Be patient, and it will give you something good.” This exchange encompassed Beverly’s outlook on both life and writing.

Beverly Donofrio is the author of three memoirs, including Riding in Cars with Boys. She’s also the author of a picture book, Mary and the Mouse, the Mouse and Mary and its sequel. Donofrio is an award-winning radio documentarian and essayist whose work can be heard on programs such as All Things Considered. Her personal essays have appeared in national newspapers and magazines, including The New York Times, Washington Post, Allure, Cosmopolitan, Spirituality & Health, and others. She lived for four years as a lay Carmelite at Nada Hermitage in Colorado, where she began Astonished, published by Viking. Beverly is now in transit, in the hallway, between here and there, a lay Carmelite out in the world, spending time with family and friends, writing as always, and teaching at the low residency MFA program at Wilkes University.

Inaugural Issue of The Cheat River Review

The inaugural issue of The Cheat River Review was published yesterday. We had a gathering in Colson 130 to celebrate. Editor-in-Chief Patrick Nuttal introduced Issue One and Editors Jessica Guzman, Mari Casey, and Sadie Shorr-Parks read from a variety of solicited and submitted work. Patric also thanked everyone involved with the journal from its foundation to its actualization, giving the well-deserved MVP to web designer (and photographer) Nathan Holmes. Check out Issue One here, and stay tuned for a second publication from this bi-annual journal in the Spring.

2013 Virginia Butts Sturm Workshop with Janisse Ray

by Rebecca Doverspike

Janisse Ray, the Writer-in-Residence for the 2013 Virginia Butts Sturm Workshop, began by reminding us that we’re all born writers. An artful storyteller, she told us about a moment when her son, Silas, was young. “He was taking half a vitamin at the time, too young to take the whole one, and one night I had him on my hip when he took his hand and tilted my chin upward toward the sky. ‘Look mom,’ he said, ‘the moon’s a half vitamin.’ That’s metaphor! That’s writing! The goal is to get back to that person you used to be.” The air quieted in our workshop as Janisse spoke. She read us poems (“The Layers” by Stanley Kunitz was one of our collective favorites), gave us William Kittridge’s essay formulation that she’s found tried and true, tended to our syntactical imbalances with insightful commentary, and always, allowed stories to seep through. “We all acquire language like a coyote. In a magic way,” she said on our first night of workshop. We spend so much time writing, reading, and thinking about writing and reading, that those moments when a comment sheds light at an angle can illumine language and our processes with it anew. I felt a pause of wonder at that articulation. Indeed, one of the marvels of a visiting writer is that s/he can give us new eyes to bring to our pages, and Janisse did just that. “Revise for strangeness,” she said, quoting Brenda Hillman. She helped us see what could be cut; she aided in precision. She paid acute attention to the level of the line: “When something’s bothering you about a sentence, you’ll usually find something grammatical,” she said, “return to your Strunk & White Elements of Style.”

Our notebooks are filled with Janisse’s comments throughout our three evenings of intensive workshops. “An essays is composed of layers. Just like a forest floor, make your essay as layered and dense as possible.” Many of us had read her first creative nonfiction book, Ecology of a Cracker Childhood, and I thought about her childhood in rural Georgia, the magic she found in her father’s junkyard and the long-leaf pine forest, and thought the connection lovely. She’d also said that while “essay” comes from the French “essai,” to attempt, the word also reminds her of “sashay,” to walk, to wander. The connection felt doubly meaningful: composing an essay involves both making layers like a forest floor and wandering through them.

We workshopped a range of material—nature writing, Norway nudism, essays written in the interrogative, short form creative nonfiction, narrative nonfiction, and the lyrical. Janisse’s aesthetic tended toward narrative rooted in scene. “Hang ideas on a person,” she said, “we’ll care about the person.” She reminded us that creative nonfiction, like life, operates through the senses.

One of the workshoppers who writes both nonfiction and poetry, Isabelle Sheperd, commented on the importance of scene when I asked for her impressions: “The workshop was incredibly helpful for my work. I’ve only recently delved into nature writing, and Ray helped me see how to combine personal details in with environmental concerns to make the essay as a whole more palpable for the reader. She showed us not just how to improve our writing, but also how to improve our lives—and how to work writing into our daily existence cohesively. I have always had trouble starting a journal, which I realize is a vast resource for writers, especially in nonfiction, but Janisse Ray showed me how to make the most of 10 minutes of journalling a day, by setting emotional moments in a scene. Ultimately, I’m absolutely positive that I’ve grown as a writer from the experience—on the sentence level, and on the life level.”

Such comments show both what Ray offered as a teacher and openness on the student’s part to integrate it into her writing and life. When we went around the table the first night of workshop to say what bird we’d be, Isabelle said, “An owl. They have a face shaped for listening.” I was an owl, too. We also had a Griffin (creative nonfiction, remember), crows, a goldfinch, seagulls, and more. There were a few times I looked around the table and saw us interacting as the bird within our personalities—fascinating.

Outside workshop, we spent wonderful time with Janisse: a ride on the PRT, a Mary Kay gathering, yoga, delicious dinners (especially the one at director Mary Ann Samyn’s house: yum!), walks, and lots of conversation. Janisse asked many questions of our lives and then reflected on her nature to ask such questions: ”...I realized his story illuminates my life.” In this way, our time with Janisse was an exchange from which we could each take something illuminating.

We had a full four days with Janisse and her presence brought a lot to Morgantown. As she read from her newest book, The Seed Underground: A Growing Revolution to Save Food , and talked about her farm in Georgia, I found that her expression of how personal connection to place is integral to her life helped me appreciate Morgantown, the place that I’ve been spending time in, more deeply. We’re grateful to Janisse Ray for visiting, teaching, and spending time with us in Morgantown—she helped us look at our lives, writing, and this place from new and meaningful angles. Thank you, too, to our teachers for bringing her here, and for their patient, persistent, dedication in teaching us.

Writer, naturalist and activist Janisse Ray is author of five books of literary nonfiction and a collection of nature poetry. She holds an MFA from the University of Montana and in 2007 was awarded an honorary doctorate from Unity College in Maine. She is on the faculty of Chatham University’s low-residency MFA program and is a Woodrow Wilson Visiting Fellow. She will be teaching Spring 2014 at the University of Montana as the William Kittredge Distinguished Visiting Writer.

Janisse Ray, reading during a workshop.

Mariah Fowler and Emily Denton during workshop.

Hannah McPherson and Melissa Ferrone during workshop.

Laughing and eating apples Janisse brought the workshop during break: Rebecca Doverspike, Sadie Shorr-Parks, and Isabelle Sheperd.

Group photo of the Sturm Workshop. Clockwise starting from the bottom left: Mariah Fowler, Emily Denton, Barett Lipkin, Rebecca Doverspike, Sadie Shorr-Parks, Isabelle Sheperd, Janisse Ray, Jessi Lewis, Melissa Ferrone, Maryann Hudak, Feagin Jones, Jesse Kalvitis, and Hannah McPherson.

Janisse Ray and Jesse Kalvitis on the PRT.

Looking out the PRT.

Jesse, pointing out places in Morgantown; she’s an excellent tour guide!

Janisse Ray and Rebecca on the PRT.

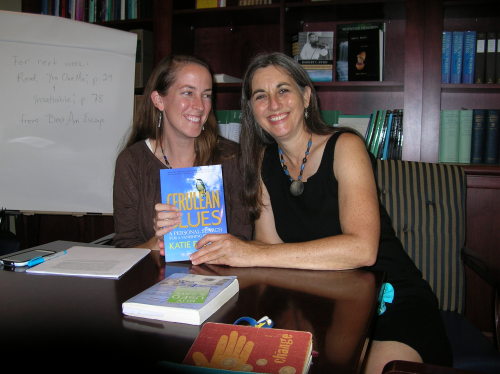

Creative nonfiction teacher Katie Fallon, giving Janisse Ray a copy of her book, Cerulean Blues (Ray had a copy, but she’d lent it to a friend named Susan Cerulean and Katie gave her a new, signed copy).

Dinner before our last Sturm workshop: Jessi Lewis, Janisse Ray, Jesse Kalvitis, and Feagin Jones.

A group photo of Janisse Ray’s visit to Katie Fallon’s nonfiction workshop.

Feed

Feed