Congratulations to Shane Stricker

Is your New Year’s resolution to read more? Hint: it should be. Keep your resolution by checking out MFA candidate in Fiction Shane Stricker’s short story, “How to Lose a Mother and a Brother in The Same Day: The Story of a Drive-Thru Funeral,” in the latest edition of Midwestern Gothic. Congratulations, Shane!

Mark Brazaitis, Radio Star

Hi, Mountaineers,

Mark Brazaitis, fiction, poet, and nonfiction extraordinaire will now add radio star to his long list of credentials. He will appear on The Diane Rehm Show at 11 am tomorrow, Tuesday, December 11, to discuss his new collection of short stories The Incurables. Mark will be in excellent company. The show, once called “the gold standard of civic, civil discourse,” has had such illustrious guests as Bill Clinton, Desmond Tutu, Julie Andrews, and Toni Morrison. The Diane Rehm Show reaches more than 2.2 million listeners and, according to their press release, “is produced at WAMU 88.5 in Washington, D.C., and distributed by National Public Radio, NPR Worldwide, and SIRIUS satellite radio.”

Mark says, “I’m thrilled to talk about my book, and about how the themes of my book connect to the work I’ve been doing at WVU—my teaching, my work with the Appalachian Prison Book Project, and my talks at the Health Sciences Center on the importance of listening to and understanding patients.”

Follow the link to find out more about Mark’s upcoming appearance.

Congratulations to Kelly Sundberg

The latest issue of Mid-American Review is out, and our very own MFA alumna Kelly Sundberg has an essay in it! Pick up the fantastic journal and read a fantastic essay by a fantastic lady.

Recommended Reading

Do you need a break from end of the semester madness? Take some time away from grading/paper writing/studying/weeping and read a poem. Here’s one by MFA alumna Amanda Cobb in the latest issue of The Boiler Journal.

And yes, that is the same Amanda Cobb who just had an excerpt of her memoir published this week in Spittoon.

Recommended Reading

Nonfiction Spotlight

by Jessi Kalvitis

When asked how their time at WVU influenced their writing, WVU’s nonfiction MFA students have a lot to say.

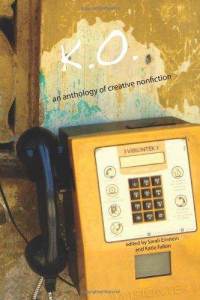

“Kevin [Oderman] has really shaped my writing,” says Sarah Einstein, who graduated in 2010, “and I know he’s had the same impact on most of his students. I wanted to make certain that, before I left, he understood the profound effect he had on us as writers, so I solicited submissions from everyone whose thesis he had directed and put them together into the K.O. An Anthology of Creative Nonfiction, with a lot of help from Katie Fallon and Sara Pritchard.”The anthology includes essays from a broad and successful group of WVU MFA nonfiction graduates, including Sarah Beth Childers, Emily Moore, Steve Oberlechner, Amy Colombo, Kirsten Beachy, Matt Ferrence, Jillian Schedneck, Erin Tocknell, Kelly Sundberg, Sarah Einstein, William Haas, Katie Fallon, Christine Lamb Parker, Emily C. Watson, Elissa Hoffman, Ami Iachini Schiffbauer, and Jessie van Eerden. The Blue Moose hosted a reading to celebrate the publication of the book.

“Some of us were writers before we entered Kevin’s workshop,” Einstein says, “and some of us didn’t yet think of ourselves that way, but we all emerged as better writers. The ways in which we were better, I think, become obvious when you read our work together. While there is a great variety in terms of style and content, the attention to detail and to language that Kevin instilled in us is obvious in every piece. There isn’t an uncareful word or a sloppy phrase in the entire book. I really wanted him to know that and to see that we are all, to a person, grateful.”

Einstein is currently a PhD candidate in Creative Writing at Ohio University. Her essays have appeared in journals including PANK, Ninth Letter, Fringe, and Whitefish Review. She is the recipient of a Pushcart Prize, and her work has been shortlisted by Best American essays and included in the Best of the Net anthology. She is also the Managing Editor of Brevity: A Journal of Concise Nonfiction.

Kelly Sundberg, a 2011 graduate, currently works as a Live Learn Community Specialist in Summit Hall, with the Resident Faculty Leader (her husband, Caleb), to develop and implement academic programming for the dorm. She teaches the WVUe 191 University Orientation course, and continues to teach English 101 and 102. She has essays published or forthcoming in Mid-American Review, the Southeast Review, Slice Magazine, Reed Magazine, flyway, Fringe, and others. In 2011, she won Slice Magazine’s “Bridging the Gap” contest and was a finalist in the Southeast Review’s Narrative Nonfiction contest.

Sarah Beth Childers, a 2007 graduate, has pieces published in the Tusculum Review, Paddlefish, SNReview, Beside the Point, and on wigleaf.com, including “Shorn” and her “Dear Wigleaf” postcard. Childers’s book Shake Terribly the Earth is forthcoming from Ohio University Press’s Series in Race, Ethnicity, and Gender in Appalachia.

Says Sundberg, “My writing matured while I was in the MFA program. After I had my son, I stopped writing for a long period, and I didn’t have a large body of work, only two or three essays. I was also very insecure about my abilities. When I was applying to MFA programs, I read an essay by Debra Marquart titled ‘Great Falls, 1976’ in Mid-American Review. I remember thinking how much I would love to be published alongside work like that someday, and now, three years later, I am being published in Mid-American Review. That’s so exciting to me, and I know it’s because of the mentorship of Kevin Oderman, Ethel Morgan Smith, Katie Fallon, and the rest of the English department faculty . . . the English department is incredibly supportive, but being a graduate student who was also a parent was difficult in ways that I probably don’t have to explain. I’m really proud of what I was able to accomplish in terms of my academic and publishing life, and I hope that my son will be proud of me as well when he’s old enough to understand what that means.”

“I struggled a lot with fiction when I first came here,” says Childers, “mostly because I really was just wanting to tell my real stories, and fictionalizing was holding me back. So many things in real life are improbable—and I struggle when I have to make things ‘realistic’ to make them work in fiction . . . In the program, besides learning what an essay was, I learned how to write a tight line, to use better verbs, to use real people as characters, to use description effectively, to tell my thoughts about a story instead of just telling the story (and when it’s not necessary).”

Recent graduates of WVU’s creative writing program are full of good advice for those of us who are still up to our eyeballs in literature classes, student emails, and endless revision. “I shouldn’t have panicked during my last year about what I would do next,” says Childers. “I wasted my energy on unnecessary despair.”

“I encourage every MFA student to make their thesis year as much about writing as possible,” Einstein admonishes. “Don’t take classes you don’t need or ask for extra teaching assignments. You will probably never again have the opportunity to work with so many kind, brilliant people who are focused on your work and you should take full advantage of it.”

Sundberg also speaks to issues of focus. “The most important thing I learned during my last year was to put my writing first. I knew that, in order to accomplish the strongest possible thesis, I was going to have to sideline some other things. That was difficult because I’m a perfectionist in most areas of my life, but for that year at least, I decided just to be a perfectionist with my writing.”

When asked for their tips for work/life balance, all three alumnae respond with bemused good humor. “By definition,” opines Einstein, “I don’t even believe that there can be balance . . . it’s okay to stop grading long enough to mop the floor once it gets sticky, but probably not before . . . I’ve finally learned how to make time for laundry and can happily report that, in my second year as a PhD student, I have not yet had to smell anything before wearing it to teach. (Weekends are none of your business.)”

Sundberg admits she hasn’t figured out the balance yet herself, and is open to tips. “My days are kind of a blur. Last week, I taught my 4 classes, graded stacks of papers, counseled dorm residents who were struggling with their midterm grades, and, along with my husband, hosted a floor dinner with twenty students, a neighborhood Safe Zone training and a Bolton Creative Writing Workshop. We also participate in lots of staff events at the dorm, and, of course, we have a precocious and energetic six-year-old. It’s all very busy and fun, but I try to find time to write during the rare quiet moments.”

To find time for writing, Childers says, “I need most of the day, since that lets me be lazy in the morning, or procrastinate with housework or reading a book and still get a lot of writing done in the afternoon. I can’t write after I teach, so I work late on those nights taking care of small, irritating tasks that will keep me from writing the next day, and I make time for some laziness (crappy TV, cookie baking, etc), so I’ll have energy to write the next day. Also, I have to remind myself when I’m working too hard on the grading that my writing matters more to me, and the sooner I get my grading done the sooner I have my writing time back.”

What does the future hold for these talented women? “This is a great time to be writing, and working with other writers,” remarks Einstein, “because the opportunities are so limitless . . . but of course that means there are also new and unexplored avenues for failure as well as success. I hope to find a professorship in the ever-shrinking world of academic employment. Like every graduate student, I read articles about PhD’s collecting food stamps and the dwindling employment opportunities for new graduates and reach for the wine bottle. It’s a scary time to commit to a teaching career. Wish me luck!”

“I’ve applied for a few residencies,” says Sundberg. “The allure of 2-4 weeks of undivided writing time was too tempting to resist. My book is nearly completed, but I’d like to polish it some more before sending it out to contests, and I could use some time to power through those final edits.”

Childers would like to “go back to England and get more ideas for a creative nonfiction book about the Brontës that I’ve been thinking about for a long time. I feel a connection with Charlotte Brontë since I also grew up with two younger sisters and a younger brother, and we all wrote together as children, making little magazines, books, and newspapers like the Brontë children did. We also, like the Brontës, wrote through play, though we had Cabbage Patch Dolls and paper dolls we made of Bible characters in place of their wooden soldiers. Like the Brontë sisters, my sisters and I lost our brother too early. I would also like to get a dog.”

In the meantime, though, she’s excited about her book. “It’s called Shake Terribly the Earth, and it is forthcoming from Ohio University’s Series in Race, Ethnicity, and Gender in Appalachia. I’m a huge fan of this series, so I felt really honored for my book to be included in it. My book is a memoir in essays about growing up in a fundamentalist Christian community in southern West Virginia. I focused on several important relatives who have passed away, including my PaPa, who drove me to kindergarten, bought me fudge-covered Oreos, and took me to see Big Bird at Sesame Street Live; my Granny, who taught me about life through Uno, romance novels, and greasy fried chicken; and my Uncle Mark, who flew kites and canoed with my siblings and me. Writing about these people made them feel less gone. My voice is influenced by Appalachian oral storytelling, since my family communicates in stories, so approachability is important to me, as well as finding humor in every situation, no matter how painful it is. In the book, I worked to capture my corner of Appalachia through our particular places, like the grass-covered floodwall next to the Ohio River, where my dad caught bugs and fished with his beagle when he was little.”

It wouldn’t be a creative writing alumnae spotlight without some book recommendations. This group has strong and delightful opinions on what we should be reading. Childers continues “to learn from the old British writers, particularly Austen, all four Brontes, George Eliot, and Trollope . . . I still love Jo Ann Beard, David James Duncan, and Brenda Miller (my grad school favorites). And I’ve been passionate about Alice Munro since I discovered her late in life in Gail Adams’ workshop. I feel like trashy Canadian girls and trashy Appalachian girls have a lot in common.”

Einstein has “been mostly reading the works of my colleagues lately, because they are such fabulous writers. Jason Jordan, Patrick Swaney, Brad Modlin, Sarah Greene, and Maggie Messitt are all writers that you should get to know!” Colleagues from WVU still figure prominently in Einstein’s reading list. “I’ve also just reread Kevin Oderman’s excellent White Vespa, and I am halfway through Ethel Morgan Smith’s equally admirable Reflections of the Other: Being Black in Germany.”

Sundberg appreciates “when female writers are willing to go to the dark places that women aren’t usually encouraged to explore. I’m tired of redemptive memoirs. I want more honesty than that.” Her recent favorites have included Lydia Yuknavitch’s The Chronology of Water and Cheryl Strayed’s Wild.

Follow the link to find out more about the Nonfiction and Creative Writing programs at WVU.

Fall Readings

by Rebecca Thomas

Colson Hall has been a buzz with words this semester. In the past few months, we’ve had no less than seven readings. Read on to find out more about them. If you weren’t able to witness the readings yourself, don’t fret. Follow the link to hear their podcasts.

Our reading series kicked off in September with Jonathan Coleman reading from West by West: My Charmed, Tormented Life a work that he co-authored with Jerry West about the legend himself. Let me tell you, anytime that I get to hear about Jerry West, Coach Wooden, and Ann Beattie, I’m in heaven.

Later that month, Katy Ryan read from her recently published anthology Demands of the Dead: Executions, Storytelling, and Activism in the United States. To read about Katy’s anthology read Rebecca Childers’ recent interview with Katy.

The English Department co-sponsored a poetry reading with Spanish poet Miguel Sapotra Bon. MFA alumna Amanda Cobb read from her translations of Miguel’s work while he read the Spanish, and at times, the Catalonian versions.

Students from the summer Writing Appalachian Ecology class read from their essays. Co-sponosred with the Biology Department, the students demonstrated the beauty of environmental writing. Who knew that soil composition could be so beautiful!

In an epic double-feature, Bruce Bond and Michael Blumenthal read their poetry in mid-October. Read Bruce’s poetry here, and Michael’s here.

Professor Ethel Morgan Smith read not once but twice this semester from her recently released Reflections of the Other: Being Black in Germany. Read about Ethel’s new book in Rebecca Doverspike’s article.

Our Virginia Butts Sturm Writer-in-Residence this year was Jaimy Gordon. Jaimy kicked off the workshop week by reading from her National Book Award Winning novel Lord of Misrule. Read more about the workshop and the program in Rebecca Thomas’ article.

While the fall readings are over, we’re eagerly anticipating the spring. In 2013, we’ll hear, amongst others, from faculty member Mark Brazaitis, MFA alumna Amanda Cobb, and undergraduate alumna Jessie Van Eerden. Check our website or follow us on Facebook to find out more details.

Recommended Reading: Dorothy Allison

Bastard Out of Carolina by Dorothy Allison

Recommended by Sara Lucas

Bastard out of Carolina has been described as the story of a family told from the point of view of its smallest member, which is true, but that’s a very narrow view of a very complex story. The main character, a lost soul named Bone, is a bastard. It’s stamped on her birth certificate. Her mother, a woman both young and old at the same time, is haunted by the state’s pronouncement but unwilling to reveal the identity of Bone’s father. Bone’s uncles have been in and out of jail for as long as anyone can remember. She has more cousins than anyone in her town knows what to do with. Bone’s life is hard from the beginning. It gets worse when her mother marries Glen, a man fallen from a family that wouldn’t otherwise associate with a people like Bone’s hard living, hard drinking kin.

Bone’s view of her relationships with members of her family, a girl that she calls friend, and the horrible Daddy Glen is the heart of this piece. Allison crafts Bone as an astute observer, breaking the audience’s heart even as she explains something in the truest way possible. This novel changed the way I view domestic violence and how it affects the development of the soul of the children involved. Bone was Bone from beginning of the novel to the end, but there are so many variations of Bone that I was constantly amazed at her wisdom and toughness.

Bastard out of Carolina is a complex, powerful, often difficult read, but definitely worth the emotional investment.

Alumni Spotlight: Wayne Thomas

by Rebecca Doverspike

MFA alumni Wayne Thomas and his students

I’ve been a fan of Wayne Thomas’ writing since we read an essay of his in Katie Fallon’s nonfiction workshop last year. The voice in the piece was unique and moving. I felt a distinct trust that he was telling us something more real than most uncover, and doing so through a voice that trusted itself. I had the chance to meet Wayne at AWP last year and found that sense of trust extended to his character as well as his work. Even in that brief time, it was clear to me that his students and colleagues have a strong relationship with him.

Wayne is currently the chair of the Fine Arts Department at Tusculum College and Editor of Tusculum Review. He holds a BA in Theatre History and Literary Criticism, an MFA in screenwriting from Georgia College and State University, and an MFA in Fiction and Nonfiction from WVU. He has been published in Sudden Stories: The Mammoth Book of Miniscule Fiction, River Teeth, and Spittoon, among others. The book he’s currently co-editing, Red Holler: Contemporary Appalachian Literature, received the 2011 Bruckheimer Award. Wayne is also the recipient of the 2012 Tusculum College’s Teaching Excellence and Campus Leadership Award and is working on a novel. Obviously, I had many questions to ask.

There’s such strong voice throughout your work. Where does this come from? How does the moment you know when a particular voice “fits” into the work at hand occur? Or is it more of an instinctual process?

Gravitas is essential to voice, and I learn that just from thinking about what I read, the good and the bad. Sometimes, you learn more from the bad. Lots of stuff out there might’ve been something if it hadn’t been given to us by the most boring person ever. I don’t mean the writer is boring, but sometimes I do. Poems and essays especially fail when writers feign that they’re perfect or their “personas” are perfect. Great ideas for stories fail all the time because writers pick the most boring characters to tell them. We ain’t gods. We’re devils. All of us. If that weren’t a fact, what’d be the point of literature anyway?

Also, I’m a Southerner, and if you want to fellowship with devils worth writing about, ride out to some porches in rural Georgia in the evening time. Listen to them talk. Listen to the way they talk. Now that’s writing. That’s poetry. Those words and rhythms compel, conjure, cajole. Like a lot of folks from the south who go for an education, the fact I was Southern embarrassed me to no ends. Felt I didn’t stand a chance, if for no other reason than everyone pointed and laughed at my accent. Now, I know it’s not anything to run from. Hell, the best writers are from the U.S. South. There’s a reason.

What of your perceptions of characters in life make their way into your writing? Which authors’ works have affected your take on life in a way that stays with you most?

The writers I admire all have one thing in common and that’s a determination to write. Flannery O’Connor talked about the habit of art. She put the phone off the hook and worked three hours a day. Harry Crews wrote every single day, even when he was drunk for thirty years. He’d get up at four in the morning when he had to, and he had to a lot cause the bottle’s less tempting at four in the morning. Tennessee Williams got up at five in the morning. The only sober part of Faulkner’s day was when he wrote. Larry Brown was a fireman all day, and then he’d teach himself to write—and sometimes work another job in between.

I think the key is learning to balance everything else you got going without letting that everything else take over or exhaust you to the point you can’t think well enough to sit at the desk. That’s probably why so many folks get up before dawn to write. You ain’t too brain dead, cause your day just started. You might be still stuck in dreamland, but that usually helps the creative process. Also, you know, if it’s your first priority, then why shouldn’t it come first?

But the thing to learn from all these folks is that determination and that balance. Lots of the kids I teach start out thinking the writing life is some sort of nonstop, self-destructive fling when, in fact, it requires ritual and never-ending durability. Certainly, you’ve got to live, to travel, to meet new people, but you also have to be okay with day-to-day humdrum—if for no other reason than you got to find time to write, time to spend with your friends and family, time to mow the lawn, and time to work whatever job you got that allows you to pay the bills. Time’s the most important thing you’ve got, because once you’ve spent it it’s the only thing you can’t get back.

I still struggle with finding that balance. I’m a little better at forcing myself to write while navigating my duties as a teacher, administrator, and editor. But there are days that I don’t, and those days cut right down to the bone. I think about all my literary heroes who worked through emotional and physical devastation and commitments that overwhelmed. On the days I don’t make time for writing, I live with guilt—and I mean guilt. On days I do, the coffee tastes better.

You’ve written literary criticism, essays, short stories, plays, and are currently working on a novel. What draws you toward a particular form or shape for your work at certain times? Which elements of craft do you feel extend to all genres?

Though I came to WVU with an MFA in Scriptwriting in-hand and wanting to study short fiction, my eventual thesis was a hybrid one, stories and essays. I’m not sure if there’s one thing that draws writers to certain forms. In fact, for the longest time, I sort of thought subscribing to one medium was self-congratulatory and certainly quite limiting, especially for folks enrolled in a creative writing program, where you go to learn to write better. Seems to me that working in script form gives you access to learn dialogue in ways other genres just don’t, as working in poetry does the same for rhythm and sound, and fiction character, and nonfiction exposition. Why shouldn’t serious up-and-coming writers submit themselves to all of these ways to figure stuff out?

I’m thirty-five and just figured out that I want to write novels the rest of my life. Can’t really explain how I came to that figuring out. This past summer, I floundered, lazily plugged away at essays and stories until one day I asked myself what would excite me the most, to feel like I’d finally accomplished something. I’ve had this idea for a novel going on ten years, and really for years and years it’s the one thing I haven’t been able to shut up about, even if most of that talking happens mostly inside my own head. So, I said, “Well, shit, I’m just wasting all this time writing these other things that I never finish. Why not try a novel? It might take a year but, with the way it’s going, nothing else’ll get done in a year’s time anyway” and I said, “So what if I write an entire novel and it fails? Really: so what? It’s not like I won’t just write another one and another one until one works out. If it were possible for me to stop writing, I’d have taken that route long ago.”

My time working in the novel form has been eye-opening and rewarding. I almost had to give it a shot before I realized how constricted I felt in the other forms. In the short stories and essays, the space just feels too narrow to get it done for me—to risk in the ways I like. I ain’t having fun unless I surprise myself, and I find it nearly impossible to surprise myself if all I got is 15-20 pages. Not to say I don’t appreciate the short forms or the people who create in them. Certainly, those structures are as necessary to their processes. Some just need fewer pages to get it done. Brecht said the best art is often a result of censorship, of imposed limitations. Oddly, I can write micro-fiction better than the short story. I can write a decent play in the ten minute format. It’s that in-between I struggle with, like I can direct an explosion in short-short spaces but am helpless to do so in short ones. Not sure if I’m making a lot of sense here. Basically, whatever form works best is innate to the individual, and writers eventually find ways to gravitate to those forms. It’s important to listen to your impulses.

You of course read a lot as an editor of the Tusculum Review. How does that process affect your writing and teaching?

Lots of writers inevitably want to put their hats in the editing and publishing ring if for no reason than to provide avenues for and to celebrate new literature. Some of my fellow WVU alumni are doing magnificent things as editors, too. Kristin Abraham and Matt VanderMeulen started Spittoon about a year ago, and that magazine seems to get better and better. Ken Robidoux started Connotation Press and publishes freaking amazing work on a bi-monthly basis. He’s published everyone, it seems, including the current U.S. Poet Laureate and a slew of the celebrated but also up-and-comers. He’s even published one of my students in his undergraduate series. All of that is fine and good, but I don’t think Ken and his editors get enough credit for the scholarship they provide about contemporary literature. Read a couple of John Hoppenthaler’s “Congeries” columns, for instance, and tell me you don’t learn something about poetics. The creative work is great, but the level of thinking about the creative processes is what impresses me the most. The folks at Connotation Press deserve a lot of credit for the dialogues they contribute to literature, and they should be applauded for their energies. I mean, from personal experience, I can tell you what they do ain’t easy, and I’ve no idea how they do it so often. All of those editors have other jobs, and they’re all working writers. Talk about balance.

In some ways, my work as an editor is merely pragmatic. We’re one of only a handful of programs in the country that ask our undergraduates to work on an international literary journal. We want all of our students to do well once they graduate, so teaching them to be editors in a real-life situation opens up more opportunities for them. Certainly, dissections about what does and doesn’t work about a particular piece helps us to understand our own writing missteps, but editing isn’t just about evaluating manuscripts, either. We cover everything from database entry to design and layout. You know, journals began as testing grounds for new writers and new work, and we try to keep that in mind. Editors at some journals look to publish every “big” name they can get, and I guess there’s a place for that. We’re more interested in uncovering folks and work that’s on the cusp of something. So many of our contributors have gone on to publish their first books. Inherently, I think this approach is most exciting for our students, as it gives them unique insight into where we are in contemporary literature.

I’d be remiss if I didn’t also say I hardly read for the journal anymore. I’m fortunate to have superb faculty peers who serve as genre editors. H. M. Patterson oversees the fiction submissions, Desirae Matherly the nonfiction, and Clay Matthews the poetry. These are all serious writers who come from the best writing programs, and they have impeccable taste and understandings. I’m lucky to have them to work with, and it doesn’t go unnoticed how fortunate I am to have so many accomplished colleagues at a school our size. I wouldn’t realize any semblance of balance without them.

You’ve received The 2012 Tusculum College’s Teaching Excellence and Campus Leadership Award. What do you find most rewarding about teaching?

Looking back at some of my answers here, I think I probably sound like a teacher. I guess that’s okay. I give a lot of myself to teaching. Sometimes I see writers use teaching solely as a means to write and that infuriates me, as I can easily credit a few of my own mentors with helping to shape me into a better human being. I don’t understand committing yourself to such a noble profession and giving a care less about what kind of job you do, and I don’t understand people walking around feeling important because they’re writers, either. We write because we have to and because we’re lucky, and we don’t do ourselves any favors not to understand that. I’m amazed by these systems we create that inevitably end up destructive to our causes. In universities everywhere, we hire “big name” writers hoping this’ll draw students into our classes. Being a “big name” doesn’t make you an effective teacher. Being able to intuit craft doesn’t mean you can articulate it. If you go to class and go home and that’s it, you’re missing the best part of teaching, which is having conversations with your students. There’s nothing better than feeling you’ve done well because one of your students does well. If you can’t humble yourself enough to learn from your students, do us a favor and quit. Go get a job as a fry cook or undefined116122.undefined116123.undefined116124.undefined116731.undefined213152.dock builder or a plumber and see if egocentricity works for you.

I love and appreciate that award, if for no other reason than my fellow teachers here at Tusculum voted for me to have it. Really, though, where our graduates end up says most about the jobs we’re doing as teachers. My students have gone on to graduate schools at Columbia, the University of Tennessee, Eastern Kentucky University, Memphis University, the University of Tampa, Chatham University, the University of Central Florida, and those are just the schools I can recall off of the top of my head. Our graduates have been accepted into a slew of other schools, too. Our graduates work at a The Washington Post, Creative Nonfiction, a couple of nonprofits, as editors, as lawyers. We’ve got a graduate studying to be a mortician, and we’ve got another studying to be a massage therapist. Not bad, too, when you consider our creative writing concentration has only been around for a few years.

I love the description of the anthology you’re co-editing, Red Holler: Contemporary Appalachian Literature, found on its Facebook page. It reads, in part: “Red Holler takes on the stereotypes of old (farmers, banjos, quilts, etc.), by instead celebrating the orneriness, earthy perversity, black humor, anti-authoritarian outlaw culture, home-grown magical realism, spirituality, and surrealism of Appalachian culture. As well, it seeks to include the voices of inner-city and mixed-race Appalachian communities and to explore LGBT aspects of the culture.” How did this project come about? How is the process going?

My buddy John Branscum and I were driving back from one of those AWP conferences and decided we liked each other enough that we really wanted to work on some sort of project together. I’d had this idea of an Appalachian-specific anthology for quite some time. I went from Georgia to study in West Virginia, and right away I noted differences in the food, the architecture, the people, the music, and the landscape. And, of course, the literature. I was constantly surprised by how folks—probably for no other reason than convenience—so often grouped Appalachia and the South. For me, it was a bit like grouping California and Florida. If anything, current Appalachia reminds me of Faulkner’s New South, with its rapidly changing landscape and economic system and its sense of individualism coupled with a new influx of people. Anyway, John and I got to talking about all of this, and we settled on what became the anthology. John gave the book its thematic quality, really, which gratefully focuses a lot on those voices folks typically don’t think to include or are for whatever reason too afraid to include. John was so excited about the project that he almost single-handedly wrote up a prospectus and had a publisher within just a couple of months.

Editing an anthology is hard work, much harder than I think either of us anticipated it being. The worst thing is really just narrowing down the contributors. There’s so much excellence happening in Appalachian literature and having to say “no” to so much of it is gut-wrenching and seems unfair even to us. But, it doesn’t take long to fill 250 pages.

You seem interested in expanding or moving beyond expectations both in your work and in editing. How do you strike that balance between writing within a recognizable genre, place, etc. and moving beyond that—expanding it? What choices are involved?

I think all those MFA programs out there have affected us in similar ways that film schools, the Film School Generation, affected motion pictures. All the time, work comes across my desk that’s pitch-perfect in craft, sometimes absolutely beautiful in language. You see this stuff published—Hell, I’ve published some of it.—and you see this stuff win awards, and you know why. But, you know, sometimes you’re just stymied to find any depth beyond the craft. There are so many devils out there who deserve outlets, and too many of us ignore these characters and stories because they seem impossible to make pretty. To do them justice you almost have to defy whatever expectations you have of craft, and for so many of us those expectations are outlined in workshop. Sometimes you just have to write a stereotype, and the more away from workshop you get the more you realize stereotypes are really only problematic when readers don’t understand how they came to be. I mean, if readers are caught up with some character and understand the character’s choices, what’s the problem? Tell Donald Ray Pollock he can’t write a stereotype.

Despite whatever years you’ve got on you, you’re a young writer if you’re in a writing program, even an MFA one. When I was in the creative writing programs, I remember wanting everyone to see me as more accomplished, more ahead of the game than the rest. What’s this accomplish, really? If you’re so good, what’s the point of spending all that money? You don’t need a formal education to write. Just go ahead and sell your book if you can. I loved my workshop experiences, and I certainly don’t aim to quit utilizing the workshop in my own classrooms. The only thing I’d say we don’t do well enough as teachers is to teach students to surprise themselves, even if doing so seems to fly in the face of everything we’re trying to teach them. Everyone’s like “take chances,” but too often we teachers don’t explain what that means, and we slap students down as soon as they do take a chance.

As a writer, I need that surprise. I require revelation to enjoy the process at all. I can’t just know where I’m going and go there—at least I can’t get there if the path isn’t brush-ridden and hard to see. Most of my characters require an acknowledgment of Southern oral traditions. There’s more than one way to accomplish that, and no one way fits every glove. If you ask multiple persons about one event, they’ve all got their own takes and interpretations. They’ll assign different relevances to what’s happened based on whatever’s at stake for them. I’m more and more invested in the way a story is shared as a community. I just hope what I’ve got to say is different and interesting enough, and maybe all this better explains my adhesion to the novel.

What is the Old Oak Festival and how have you brought it back to life?

I moved over as chair of English to chair a newly-created chair of Fine Arts Department. The fun part of this administrative kind of job is finding ways to advertise and push your programs. I’d always wanted to do some sort of festival that focuses on fine arts. Twenty years ago, there was this thing called the Old Oak Festival at Tusculum. I’d heard about it through various alumni I’d met along the way and discovered it was quite a big deal—at least in our area of the world. The Old Oak Festival from long ago was comprised of lots of arts events, mainly live bands that’d come to campus and play throughout the weekend. Talking with the alumni, whose eyeballs widened with nostalgia whenever they reminisced about Old Oak, I realized bringing this festival back could be a hit. Our Institutional Advancement people got behind the idea quickly, and we ended up with a weekend festival made up of a couple dozen live bands on the campus lawn, creative writing readings, the launch of our newest issue of The Tusculum Review, visual arts and digital media exhibits, a theatre performance. We had artisans, books signings, and food vendors. I think everyone had a good time.

My favorite part of our inaugural festival was hosting Katie Fallon, another WVU alum, for a reading to celebrate her new fabulous book Cerulean Blues. Katie’s one of my favorite people in the world. I’m proud to have graduated from the same school and program as she did. Somehow, that gives me a sense of accomplishment.

I’ve read that in the spring you’ll be directing Theater-at-Tusculum “Experimental Theatre- 10 Minute Plays.” As a writer and editor, I imagine you’d have unique insight into directing. What do you enjoy most as a director?

We’re working on a theatre degree here. A theatre program offers some of the most essential academic offerings on a college campus, as theatre is inherently interdisciplinary. If done right, theatre combines heavy amounts of research of whatever play and subject matter is at hand, math and science in set design and building, music, writing—really, anything you can think up.

Of course, I’m an advocate because my undergraduate degree is in theatre. Initially, I agreed to direct because I wanted to bring in a visiting playwright. What happened in the end might be even better. I had so many excellent short plays come out of my last Scriptwriting class that it became apparent we should produce at least of few of them. So, that’s what we’re doing, plays penned by our very own students. Should be a lot of fun. More importantly, it’s a chance to advertise our students and programs.

There was a time I felt like I was a better director than writer. You know, I’d recommend theatre to anyone interested in writing. To do theatre well, you’ve really got to investigate character motivations. You’ve got to know what’s at stake for everyone at every single line. When you get into dissecting the choices playwrights make about characters, setting, story and plot, and all those other craft things, you quickly realize that none of the thinking that goes into making a single decision is arbitrary. More importantly, you appreciate how nothing can be arbitrary if you expect to have any success at all. This is true in the theatre world, and it’s true for any art.

How have you found ways to balance being an editor, administrator (director of the Fine Arts Program), writer, and teacher (as well as a person outside all of that, of course?)?

Finding that balance is a theme in our entire conversation, isn’t it? I think a lot of it is finally realizing there has to be a balance. I spent years where, at the end of the day, I said, “Damn, I didn’t write today. When did I have the time to write? When will I?” You live like that long enough, and you begin to wonder why you do anything you do. If you don’t write, everything else comes to seem pointless. Seriously, writers have to write. As I tell my students, if you can quit writing, you should. I don’t mean that dismissively or anything. I’m not the first to point out it’s a difficult lifestyle—full of self-doubt and rejection. But, if you have to write because you can’t quit and you find yourself not writing, you start living with this guilt that can easily turn into self-hate. Eventually, you realize this can’t go on, and you seek out that balance. You start demanding of yourself those hours, or hour, or at least a few lines; whatever you can manage in a day saves you from nothing. You learn that everything else will be there tomorrow. More importantly, so will the writing, the best part of the day. You just plug away, figure it’ll all get done eventually. It will, even if the thing you have to write is a novel that’s apparently longer than most. And, always, you hear Flannery O’Connor, whispering in your ear, “A gift of any kind is a considerable responsibility. It is a mystery in itself, something gratuitous and wholly undeserved, something whose real uses will probably always be hidden from us. Usually the artist has to suffer certain deprivations in order to use his gift with integrity.”

Wayne Thomas is the currently chair of the Department of Fine Arts and associate professor English at Tusculum College. He is the 2012 recipient of Tusculum College’s Teaching Excellence and Campus Leadership Award. You can find his work in Sudden Stories: The Mammoth Book of Miniscule Fiction, Spitoon, and River Teeth. He is also the co-editor of the Appalachian literature anthology Red Holler.

Marsha Bissett: The Calm Behind the Scenes

by Rebecca Doverspike

As we attend readings, workshops, and award luncheons throughout the semester, we sometimes forget there’s behind-the-scenes planning necessary to form those events. Marsha Bissett is one of the crucial people behind those scenes helping to make sure such events run smoothly. We wanted to highlight her invaluable role in the department by asking her some questions about her work and perspective.

1) What path(s) brought you to work in the English Department at WVU? How long have you worked for WVU?

I came to WVU in March of 1990. I accepted a position as Administrative Secretary in the Department of Foreign Languages, where I remained for 14 years. In the spring of 2004, I accepted a position as Program Assistant in the Financial Aid Office, where I remained for 2 years. In August 2006, I accepted my current position as Administrative Assistant in the Department of English. I have been at WVU for a total of 22 years.

2) Could you give us a brief description of your job?

I plan the departmental events, such as readings, lectures, workshops, and seminars. I also coordinate the awarding of scholarships and writing contest prizes.

3) What is a “regular” work day like—the tasks involved, etc.?

I really don’t have a “regular” work day; it just depends on what type of event I’m planning at the time. A typical reading involves reserving a room; making a hotel reservation for the guest, if needed; publicity, such as a press release and poster; contacting the WVU Bookstore and asking them to purchase the books to sell at the reading; ordering refreshments; making a program; and setting up the room the day of the reading. The Writers’ Workshop requires year-around planning, such as reserving meeting space and preparing publicity in the fall semester, to accepting applications and corresponding with participants in the spring semester, to making final preparations during the summer.

4) You organize a lot of events and communicate with a great number of people (and, from personal experience, always with warmth)—how do you keep all the pieces in place in the midst of all these interactions?

After being in this position for six years, I’ve learned that you always have to plan ahead. I use my Groupwise Calendar to keep me on task. This way, I know what I have to do and when it needs to be done. I try to treat everyone with respect because I know that’s how I would like to be treated.

5) What is the most rewarding aspect of your work?

I think the most rewarding aspect of my job is the feeling of satisfaction when an event, that I have planned, is successful. It’s also a pleasure to award scholarships to deserving students.

6) At which times do you feel stressed or overwhelmed? What do you keep in mind at those times?

I feel most stressed during the latter part of the spring semester. This is when the scholarships are awarded, the writing contests prizes are awarded, and I’m planning the Awards Luncheon all at the same time. It can be a little overwhelming, but I keep thinking about the summer break and that seems to help.

7) Do you feel you’re part of a larger team or do you feel independent while you’re working (or maybe a combination thereof)?

I feel that I am both part of a team and independent. In order to organize a successful reading or workshop, I rely on many WVU employees to do their part in the process. Some of our events are held in the Mountainlair, so I rely on the Reservations Office to setup the room. I rely on the Catering Office to supply the refreshments. I rely on the WVU Bookstore to have the books to sell at each reading. It’s sort of a group effort, even though I am responsible for getting in touch with each office.

8) Could you tell us a story of something that’s happened during your job that you’ve never forgotten?

One spring semester (I forget what year); I planned the pizza party for early March. This is an event where undergraduate English majors can come and enjoy pizza and receive course flyers for the upcoming semester. The weather did not cooperate that year and we received a huge snow storm the day of the party. The pizza had already been pre-ordered a week in advance and there were few students that showed up for the party.

9) You’re known in the department for being ever-kind and calm. How do you always attain such calmness?

Sometimes I think it’s just your personality that controls your demeanor. I have always been a quiet/calm person, even as a child. I’m definitely an introvert. Also, I try not to allow small mishaps to upset me.

10) What do you like to do outside of work? Any favorite authors?

I like to spend time with my husband and our two sons. We enjoy hiking, bike riding, family vacations, and picnics. I don’t have much free time to read, but I do enjoy reading magazines such as Family Circle.

Throughout the department, we know how invaluable Marsha is.”Marsha Bissett is so utterly reliable and unobtrusively thorough that it’s easy to forget how much she does to support the outreach and public perception of this department,” Jim Harms said. “She really is indispensable. She’s also as decent and kind a person as you’re likely to meet.”

Mark Brazaitis agrees. “As the director of the Creative Writing Program and the West Virginia Writers’ Workshop, I have worked closely with Marsha for the last five years,” he said. “I couldn’t ask for a more dedicated, considerate, and talented colleague. Marsha is the secret magician behind so much of what we do. For our reading series, she drafts press releases, designs publicity materials, and creates programs. She also helps with the logistics of bringing writers to campus. For our undergraduate program, she collects submissions for the Sturm Scholarship, publicizes Calliope, assists with the awards banquet, and so much more. For the West Virginia Writers’ Workshop, she does everything but read at the open mic. Maybe this summer! It’s a huge gift to have Marsha in our department.”

The next time that you’re in the English Department, stop on by Marsha’s office to say hello and thank you for all of her wonderful work. Better yet, say thank you to everyone that works in the office. We’d all fall apart without them.

Feed

Feed