Kevin Oderman on White Vespa

by Rebecca Thomas and Rebecca Doverspike

During nonfiction workshop, Kevin Oderman assigns each student one aspect of a work to consider: structure, content, or voice. In doing this, he makes us think critically about the craft. For us, this resulted in some of the best writing of our lives.By focusing so specifically on one element, we learn to pay attention to every detail. We learn how to mold and craft piece of work. We become careful writers. This doesn’t mean careful as in afraid to take risks; no, it is the exact opposite. We learn to take care with our writing, be thoughtful about it, and, just as important, to take ownership of our own style.

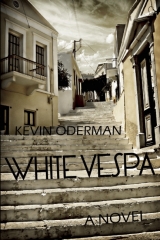

It’s no wonder, then, that the people of Colson Hall (both past and current students) have been a buzz about Kevin Oderman’s latest novel, White Vespa. According to Etruscan Press, the novel’s publisher, White Vespa is the story of “an American expatriate [who] hopes to quell his grief for a long lost son in the stillness of his photographs of the Dodecanese Islands. But soon friendship and then love for a woman wounded in her own family-born grief propel him toward life again, where stillness is set into motion and identity might be recovered, against odds, in a foreign place” (Etruscan Press).

The word’s out on White Vespa. Alumna and novelist Jessie Van Eerden says, “This is a book you savor, written in short lyrical sections that are at once spare, suggestive, and so multi-layered; the dialog especially reads slowly in my mind as if I am right there on Symi looking out at the water, in between bites of cheese and rough bread, listening, along with the characters, for all that’s unsaid beneath speech. How does Kevin achieve this intimacy, not only among characters who are travelers, strangers to each other, but also with the reader who is a stranger among these private and often wounded people? Perhaps by manifesting on the page so thickly and beautifully their longing for connection, each short chapter coming into being like one of Myles’ photos in the dark room revealing another dimension of that longing. From one of the italicized sections in Myles’ voice: ‘I watched slow smiles pass from face to face, I saw again how people care and find each other, if not forever, for awhile’ (128). Yes, there is a sense, too, of the ephemeral nature of connection. This is a beautiful book.”

We wanted to find out more about Kevin’s novel and his writing process, so Rebecca Thomas recently asked him a few questions.

RT: I’ve been reading a bit about your novel, and I’m really interested in hearing how the novel came together. I’m trying to avoid the word inspiration, so I think I’d like to know what drew you to the work. It’s always interesting to hear how subject matter calls the author.

KO: My answer to your question may not be useful, but here goes. The book started with an image, a clip of memory from when I was fourteen or fifteen years old. In it, I’m walking through a Safeway grocery store on N.E. 122nd & Glisan, in Portland, with a couple of other guys. One of them I don’t know too well, an older kid, magnetic, handsome, and we walk up behind a young mother dragging a little boy by the hand behind her, and the handsome kid trips the little boy, who falls face first onto the floor, and cries out, and the mother berates the boy, and the handsome kid, skirting by unnoticed, laughs, enjoying his meanness.

The tripped boy probably got over it in a few minutes; me, I’m still worrying that memory almost 50 years later!

I used the scene in White Vespa, near the end of the book, but I plucked it out of long-ago Portland and sat it down in Bodrum, on the coast of Turkey, in the summer of 1996. And, more importantly for the story, the character Paul grew from that bit of gratuitous meanness in the Safeway, and then Paul shaped a good deal of what happens in the book.

All of which must sound pretty roundabout, but the imagination, I think, is no great friend of the straight way. Indeed, what’s atypical about this example is that I kept the scene, the tripping.

RT: While I was in your class, you really helped me become more aware of structure. Structure in any genre always seems like a puzzle, figuring out how moments speak to each other best. Can you talk a bit about the structure of your novel and how it came together?

KO: “How moments speak to each other best,” that’s so well put! Don’t be surprised if I appropriate that formulation in class…

Structure. I’m not a natural storyteller. So when I sit down to write fiction I’m thinking about story from the get-go. In White Vespa, I worked hard to generate narrative pull out of the structure the story. The book is composed of many short chapters. Most of these chapters track one or another of the story’s main characters (close third) through a scene or two. And then a jump to the next chapter. Those jumps allow me to create narrative speed without car chases. Scene, scene, and almost no summary. In place of summary, doing some of the work of summary, I have comment, comments by the characters (they are a bunch of talkers) and comments from the central character’s daybook. Myles’ daybook. In the linear timeline of the book, the daybook entries come at the end, but I shuffled them in from the beginning, to register the impact of the summer’s events on him and to give the book more felt inwardness.

White Vespa is set in the Dodecanese islands, the Greek islands just off the coat of Turkey. Most of it takes place on Symi, but there is an excursion to Tilos and the book ends on Nissyros. Little islands, little worlds, places that feel comprehensible and yet suggest the big world, too. And these little Greek islands are quite seasonal, they awaken in May and return to sleep in September. I like that condensed year, the way it heightens the felt transience of things.

There is something of the enchanted isle in every Greek island, and deep down I suspect that The Tempest is churning the weather in White Vespa, though that never occurred to me while I was writing the book.

RT: I also wonder how you find the balance of drawing from “real life” as a fiction writer. I think of this in terms of your work as a nonfiction writer, too. Does the writing process change at all writing in different genres? How did you know that fiction was the right fit for this story?

KO: As a reader, I appreciate the energies that authors can generate out of the many ways in which fiction and nonfiction overlap. Ambiguities that won’t be resolved keep their charge. But, as a writer, I’ve not been called to such work. My nonfiction is strictly constructivist, built out of experiences, and on the occasions when I’ve thought imagination was called for, as part of the experience, I’ve made it clear where the imagined bits begin and end. And, writing fiction, I have included very little of my own experience, almost none. The places, however, in both Going and in White Vespa, are there. It’s important to me that they be there, though I’m not quite sure why, and I recognize that the way I see Granada (in Going) and Symi in White Vespa colors those places quite distinctly in my descriptions of them, probably out of all recognition in some cases.

Anyway, the simple answer to your second question is that I knew White Vespa was fiction because it only happened in my head.

The writing process, fiction, nonfiction, is more or less the same, involves sitting in a chair, waiting for some words to turn up, and then messing with them.

RT: I was curious about your writing process for this novel. How did the project evolve? I can only imagine how time consuming teaching is. How do you find the balance between teaching and writing? So many of us MFA students are terrified of being able to find the time to write once we graduate.

KO: Well, I doubt that the demands on my time are any greater than the demands on yours. And I haven’t found a balance between teaching and writing. I don’t even feel them as competing demands that often: I do the teaching first. That decision is made before I get to choosing. And, because of that, I don’t feel torn and certainly not terrified.

I have mostly written during the many breaks in the academic calendar. I have written best off by myself away from Morgantown. Could I have written more if I wrote all the time, no doubt, but I’m not so sure I would have written better. I like to imagine, anyway, that, working slowly, I’ve been able to find my way further in to what I have to say in a novel or indeed in an essay. For me, persistence is the cardinal virtue.

That said, I don’t think my way of doing things is best or even admirable. It’s just what I find, looking back, that I have done. Every writer I’ve met seems to have found a way around the constraints on imagination. And every one seems to have found a differents way. You’ll find your way, too; I’m confident on your behalf.

The generosity in Kevin’s last answer is seen in everything he does: his time and attention to drafts in workshop, his thoughtfulness about writing, and his own work as well. It only seems inevitable then that Kevin Oderman would end up with, as Jessie Van Eerden says, “a beautiful book.” Luckily for us, White Vespa is just that.

Feed

Feed

Comments disabled

Comments have been disabled for this article.